Three Tones of Virtuosity at Circusstad Festival 2025

In sunny and warm spring weather at the Schouwburgplein in Rotterdam, Circusstad Festival 2025 presented its 15th edition from the 30th April to the 4th May, with a selection of local and international shows and happenings. From the local scene, this edition included shows from youth circus groups from around the Netherlands, like Sold to the circus, works in progress showings by current CODARTS students and recent graduates, as well as the interesting project Buitengewoon, a festival co-production together with the maker Liza van Brakel, in collaboration with the local Theater Babel, which sees four professional circus artists together with four players with intellectual disabilities. From nearby countries, there were the shows Ballroom and Man Strikes Back from the Belgian Post Uit Hessdalen, iRRooTTaa by Grensgeval and Circus Katoen, and OMÂ, or the privileges of the potato by German-Iranian foot juggler Roxana Küwen Arsalan. Going (far) more international, the programme included the Rise of the Olive, a combination of circus and stand-up comedy from New Zealand by the trio Laser Kiwi. To round everything up, Laser Kiwi, alongside Captain Frodo’s Family Freak Show performers Lisa Chudalla and Melisa Meijs, joined their powers in Late Night Cabaret presented by Harvey Cobb of Headless Productions.

During my visit, I chose to take a closer look at three of the main shows: Ákri by Manel Rosés, RECLAIM by Théâtre d’un jour, and KA-IN by Groupe Acrobatic de Tanger, directed by Raphaëlle Boitel of Cie. L'Oublié(e). Circustaad offers a variety of nuances of virtuosity, and this aspect shaped my reflections in this report, opening up space for discussion on the art form.

A sad jester questions virtuosity

Ákri (άκρη) is a Greek word that translates as threshold or boundary. It is the first part of the word acrobatics (ακροβασία), which means "walk on the limit" or "walk on the threshold". It is also the circus solo of Manel Rosés, an acrobat from Barcelona, who is bringing Ákri to Circusstad, to speak about time and space and how we experience them. Speaking is one of the medium Manel uses during the performance, talking in English to the international audience in Rotterdam. However, before that, let me describe what is happening on stage(or, off?).

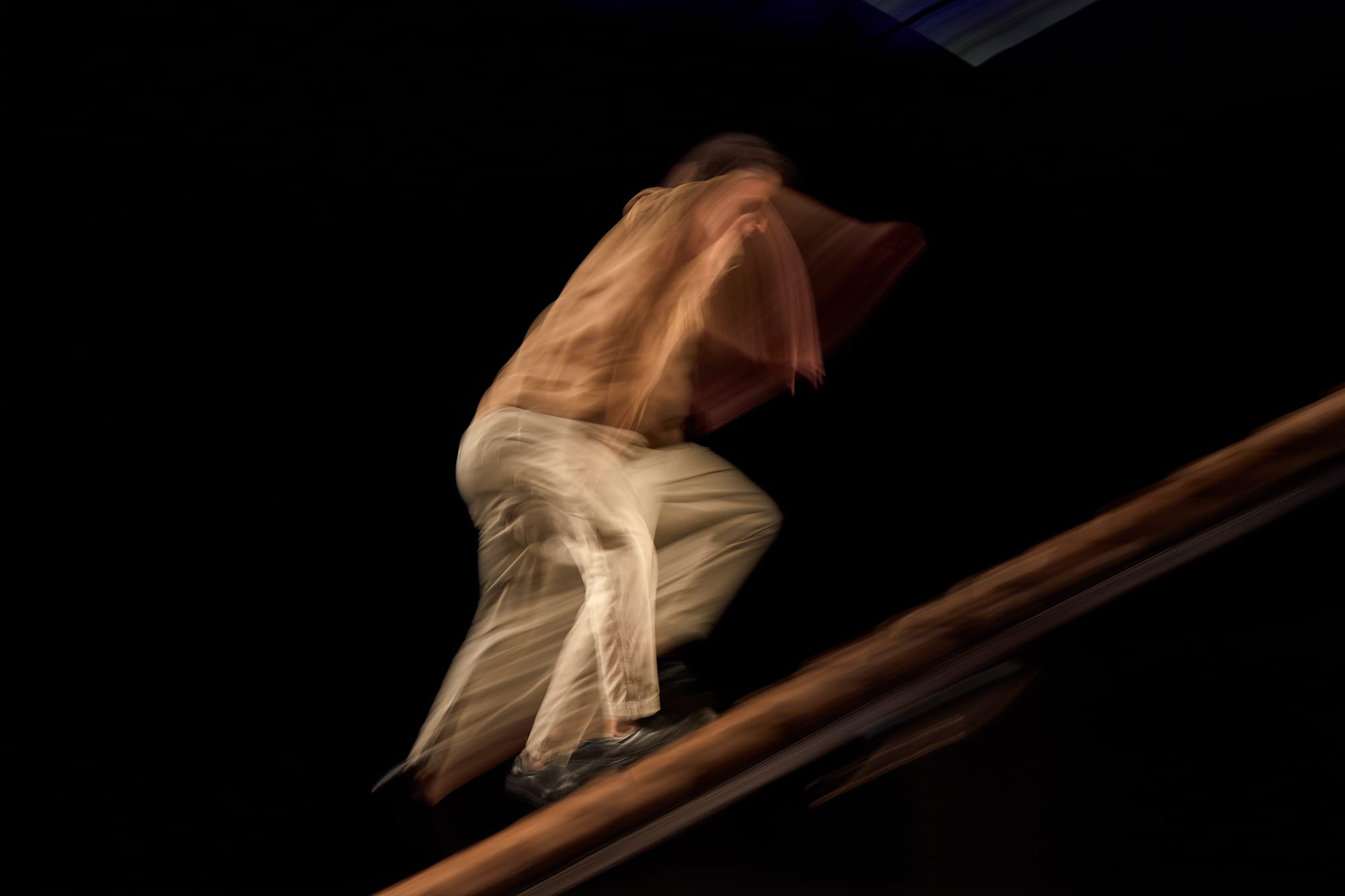

First, Manel is seen coming out of a door onto a staircase. He tries to climb it bit by bit, slipping, stumbling and falling multiple times. It resembles the traditional discipline seen in circus, in which a clownish-cascadeur character is repeatedly falling and struggling to get back up, because of some invisible slippery surface or unexpected obstacle or danger. Manel follows this traditional pattern of slapstick and succeeds in falling and gaining some laughs from the audience, including some young members. He seems to have mastered the art of falling, making it look smooth and effortless, as if instead of stumbling and falling down the stairs, he’s landing on a mattress. More recently, this pattern was seen in Yoann Bourgeois’ dance performance - installation Mechanics of History of a rotating circular stairway with a discrete trampoline.

However, as soon as Manel reaches the top, the question becomes ‘how do you get back down?’ And what does it mean to reach the top? At this point, Manel becomes aware of being seen by an audience. He already knows he is performing and decides to break the fourth wall of representation, of being "in". He decides to bring the audience “in” to what he’s doing and shares his reflection on what it means to be ‘on stage’ and what is expected of the performer. “A person goes on stage or enters a stage?” he asks. When are you “in” or “out”? He claims that if he has to think about what to do next, he’s not fully immersed in playing. He is sort of ‘acting’, based on what a virtuoso acrobat or artist is expected to do in this case. Perhaps implying a reference to Yoann Bourgeois, Manel Rosés is not just aware of the poetics of falling that is culturally embedded in it and similar performances and installations, but he is showing an irony towards it. He’s already mastered it, so he can question it.

He proceeds to do plenty of headstands, handstands, acro dance choreography patterns alongside lots of surprises and ingenious tricks, such as juggling with the same slippery shoes he was wearing at the start. While doing these, Manel often stops to echo his reflections, getting deeper and deeper, as he is still not fully satisfied…still not fully "in". "The moves are stolen, the music is cheesy." He expresses his wish not to do what people like for once. It is as if he, like every artist, is trying to please an audience, but the fear is seeping in.

In the meantime, the whole scenography changes, more doors are added, and we see Manel getting dressed into a sad jester red costume and sitting on an armchair. The actual painting inspiration is on stage as well. It is called Stańczyk, the most famous painting by the Polish painter Jan Matejko, finished in 1862. In this painting, we see the contrast of the jester sitting on an armchair at the centre of the picture, being pensive and sad, while there is a lively ball going on in the background. Now, he is "In". We hear the creator’s or the artist’s voice saying how often they want to leave, how they want to change, and how it is all between fear and desire; about doing everything and nothing at all. Eventually, the jester is sad because he’s no longer happy in making people laugh by doing the cheap clown tricks.

In Ákri, the staircase is both the apparatus and the scenography, and this threshold it represents is a passageway between two spaces, and at the same time, it is a trade and a way of life. Manel Rosés walks through the threshold and questions how. He plays with the conventions of what is expected to be seen. He knows all the tricks, he follows the trends. His technique is really on point, so much so that he impressively finishes a tough acro-dance sequence and then speaks as if he didn’t break a sweat. He also proves to be a very adept speaker, explaining clearly and articulating his thoughts really well. Even though he wishes he wouldn’t think, he would just play.

Ákri lies in the mix of disciplines between acrobatics, theatre, object manipulation, and clowning. More than that, though, it is a show staging an existential meta-reflection on contemporary circus and being an artist in general. It is about a virtuoso artist who is a master of stunts and failure like Sisyphus, tired of cheap clownesque tricks, while being aware and making fun of the cheesy virtuosic "reassuring" performative character of circus, showing what is happening behind the scenes. In the end, though, it is deeply about being human.

An ancestral mysterious virtuosity

Reclaim, by the Belgian company Théâtre d’un jour, is an imaginary ritual performed in the round. It was designed to be performed in an intimate tent, but due to a malfunction during the set-up, the company performed in the same circular set design in the open air, a singular condition that gave the show a unique outdoor atmosphere, exposed to the daylight.

Reclaim is performed by an opera singer, two cellists and five acrobats, combining opera music with hand-to-hand acrobatics and some physical theatre elements. The show is not meant to be just a performance but an experience, as the company proclaims to create an act of resistance, making the show a kind of ritual which provokes and invites the audience to imagine a sustainable future. It is, as I read in Joost Goutzier’s piece, "lightly based on shamanic primal rituals of the Ko'ch peoples of Central Asia, who want to eliminate the inequality between men and women to achieve a better world for future generations." Patrick Masset, the Belgian artistic director of the company Théâtre d’un jour, came up with the idea after reading Le ciel et la Marmite (roughly translated as ‘Heaven and the cooking pot’), a book by Sylvie Lasserre about female shamans."

Following this context, in Reclaim, the audience are spectators - and not yet aware potential participants - of the ritual the performers have set up. They are spread out, sitting between audience members. The performance starts with the five acrobats entering a folk-dance sequence, stomping, grunting, and moving rhythmically, while soprano Blandine Coulon sings a folk song, beating a drum. They are slowly transforming into wild feral animals, putting on skull-like masks and fur, becoming dog-like characters that know no boundaries of contemporary society. The raw and elemental qualities are there, as the group goes into a prehistoric chase, violently grabbing and lifting each other, using partner acrobatic skills, and going next to the audience. They even jolt, push, or slightly discomfort the audience, as they remain faithful to their animalistic presentation. It is clear that this violent scene, which includes some primal screams from acrobat Chloe Chevallier, brings the audience into discomfort, as they are unsure how to react to all of this. Some are stupefied, others are shocked, scared, or moved. We see her as the ceremony’s leader, holding a doll in the shape of a child, whom she hides and shields from the animosity that is about to ensue.

The ritual moves onto having more subtle moments in which tension is building and the performers lift each other, do somersaults, flips and pyramids very close to the audience. One of them is also spinning a huge axe in front of the audience’s eyes. This proximity succeeds in raising the tension, and the performers show an ability to master the space and the risk that is involved. As a result, the spectators slowly start overcoming their fear and trusting the process through the artists’ virtuosity in tricks. Music plays a crucial role in setting the atmosphere, as the opera singer is sometimes another leader of the actions. She’s lifted and carried around on the shoulders of other performers while maintaining an impressive quality of her ethereal voice, echoing around folk baroque melodies from around the world. Her voice is strong and can be heard even in the openness of a busy square, instead of the closeness of a tent, as it was planned. Similarly, the two celli are also mixing with the acrobats, as one of the two musicians is lifted to play seated on an acrobat’s shoulders while he stands on top of another performer.

Progressively, it becomes clearer and clearer that the performers want to involve the audience in their ritual. We need to learn the steps, learn their history, and become part of the tribe, perhaps. A few are lifted, others are addressed personally in different languages, in a whisper, or a song. They are invited to lend a hand, to support, and build a giant pyramid in this intimate setting. One phrase stands out: "The future is not what will happen to us, but what we will do." At the show’s end, the child is brought back and protected to reach the top.

While the performers are holding a ritual that they have created, and all the elements (props, costumes, music, grunting, etc.) are representing a non-Western kind of ritual of another time and dimension, the Western audience seems not to have the tools to decode what they are experiencing. The lack of decoding tools for the audience not only becomes clear in their varied reactions to the "imaginary ritual", but also in their expected role. Are they witnesses to an important event taking place? Are they invited to be initiated into the tribe, or to co-create the ritual? I perceived a clash of cultures and of time and space, which hinders the skilful blending of the limits between physical theatre, partner acrobatics, opera singing and immersive performance, as well as some brilliant moments of great artistry and high skill acrobatic patterns, and moving soundscapes and music atmospheres. In different moments, it is comforting and discomforting, wild and tender, raw and visceral, but certainly, compelling.

A subtly political chiaroscuro virtuosity

KA-IN (literally translated as being, life) is a meeting of worlds. On the one hand is the Moroccan Groupe Acrobatique de Tanger, which has become renowned for highly skilled, fast-paced acrobatics and innovative, multidisciplinary creations. Their roots rest in the centuries-old tradition of human pyramids and acrobatic stunts, originating from the nomadic Berber tribes. On the other hand is director and choreographer Raphaëlle Boitel of Cie. L'Oublié(e), whom the company invited to direct. Her work is known for mixing theatre, circus, dance, music, and film, alongside the set designer and lighting designer Tristan Baudoin and the composer and musician Arthur Bison.

In the introduction talk before the show, between Circusstad artistic director Menno van Dyke and Raphaelle Boitel, she explained more about her aesthetic choice of playing with different styles of lights, quoting the chiaroscuro painting effect used by Caravaggio as an exciting example, where darkness and light meet each other. In what can be mistaken as a more introspective approach that goes against the all-out energetic style of Groupe Acrobatique de Tanger, she emphasised a path from darkness to light.

The group itself is of Moroccan tradition and roots, but is very much French-based and established, travelling around the world. The company was founded in 2003 by Sanae El Kamouni, and they like to invite a different artist to direct each creation. That’s how Raphaëlle was invited, through common connections and interest in each other’s work. She highlighted her awareness and worry not to impose a French European vision on them, which is why she went to Morocco for the audition of the production in Tangier and had a first residency together with the group in Marrakesh, to meet the people, the culture, and the country. Through the audition, five new artists were added to the others that have been with the company for longer.

She mentioned how fully involved and ready the group was to jump right in with her ideas and vision, even if it involved coming to touch with their emotions and proposing ways of expressing their ideas, which they might not be so used to in their education and urban dance/street background. She also said that despite their excitement and hope, obstacles were coming from their society and relationships, such as the difficulty of finding many female artists in Tanger, and the way gender roles are expected to be seen. In KA-IN, there are three female and ten male performers, and she hoped she could bring them from darkness to light. For her, KA-IN is about the contrasts, the absurdity of daily life. And she hopes to bring the audience on a journey.

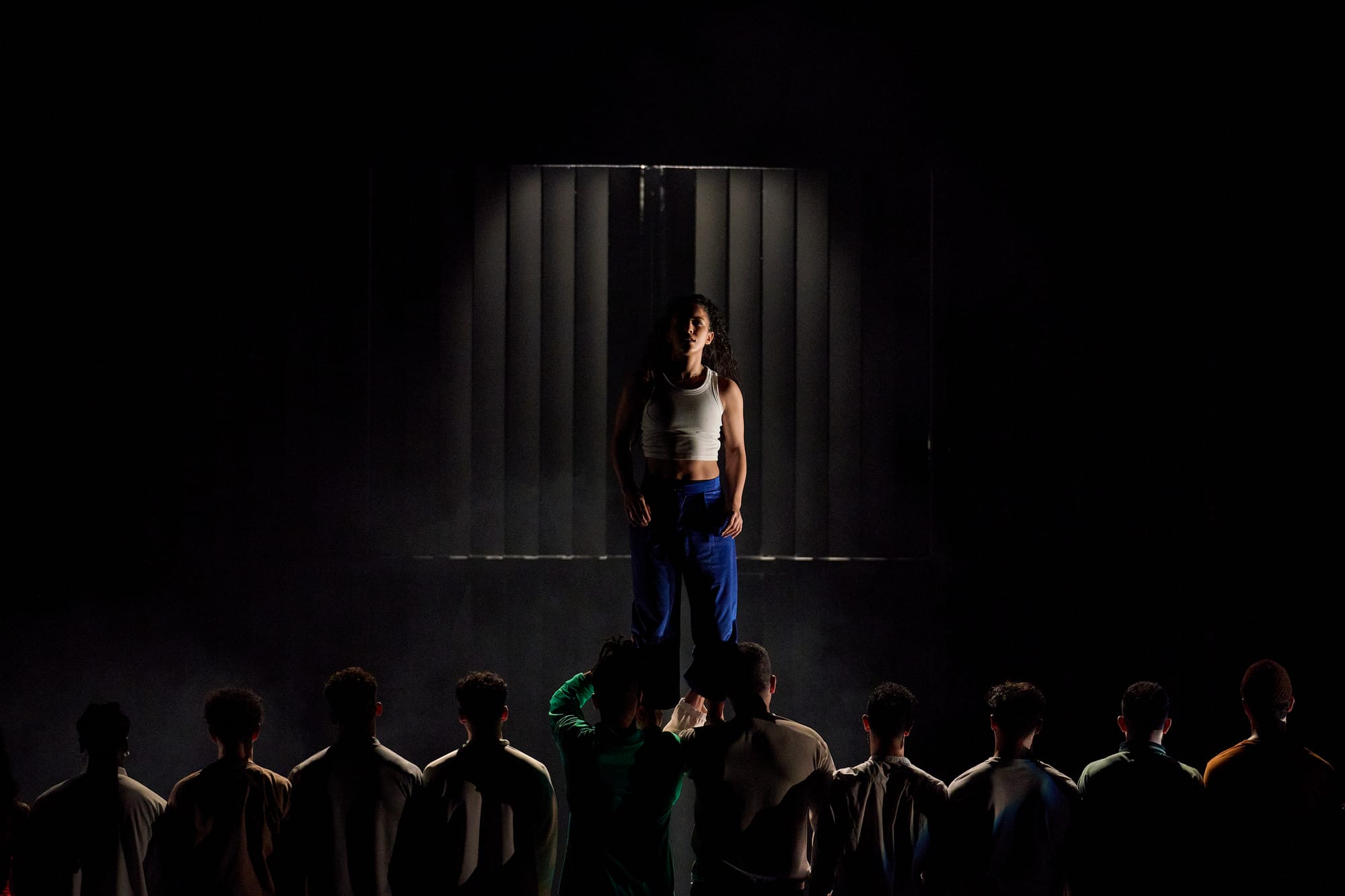

On stage, we see 13 acrobats and break dancers representing many scenes from their lives. The stage is like some neighbourhood of a Moroccan city where young people meet to dance, express themselves, and are also able to confront each other openly. They stroll around, meet up, and run into each other, as small stories start coming to life. We start discerning some characters in the group, such as a sort of neighbourhood leader figure, who feels responsible for keeping the rest of his peers in conformity. He is there to "police" behaviours and make sure everyone is aligned, almost like soldiers. Even when another one of them tries to make fun of this ‘leader’, he eventually falls in line. Even when a female performer tries to escape from the group and move over the imaginary wall they have created by stacking their bodies next to each other, it proves harder than expected. In the same way that their acrobatic techniques were once used to climb over the walls of their enemies, the group is now sending its members to cross over imaginary walls through their art. Then, the female character eventually manages to walk over the wall by walking on the arms of her peers. She walks on the hands of men. In another scene, we see a duet between a male acrobat and a female dancer. He lifts her and twists her around his body. The intimate and tender connection they seem to have at the start is then broken up by his behaviour, which leads to an angry and sad outburst from her.

The performance’s storytelling is all about human emotions and their absurdity. We see friendships, relationships, love, joy, despair, sadness, disappointment, fun, teamwork, hardship, and discipline, to name a few. Even if we don’t understand their language, the topics are deeply human. They are revealed to us in the "chiaroscuro" stage and light scenography, which are minimalist but very effective. The only scenography consists of curtain slats, through which light occasionally shines. That light, though, is not stationary, but rather it is multilayered and moves vertically and horizontally, to give us many different atmospheres and styles. It literally creates spaces, shadows, and a lot of shapes, in which the performers play. It is further amplified by a variety of lights all over the stage, from strobe lights that create a stop-motion effect to the movement of three dancers, to a strange snake light that slowly ‘comes into life’ and becomes a powerful organism after being manipulated by a performer. A very powerful scene is created just by the use of many bright flashlights in an otherwise completely dark stage, where one of the performers is surrounded by the flashlights, which corner them from every angle, moving rapidly from side to side, up and down, similar to the performer’s movement, going to a slow climax. It is interesting to note that this is the only black performer in the group who becomes the target, the victim, before being invited back.

KA-IN is indeed a meetup of the traditional style of Groupe Acrobatique de Tanger, with a clear director’s hand from Raphaëlle Boitel of Cie. L'Oublié(e). Her approach makes it cinematic and fascinating, coupled with their amazing energy and endless somersaults, pyramids, and backflips. It is not only that, though, as their emotions can also be seen in their multiple stories. In the end, the artistic mixture is layered and enriched. We see another kind of virtuosity. It is a group that, through the expressed intention of a director not to neglect their roots but help them express them and bring them from darkness to light, is willing and perhaps obsessed to abandon its preferred form, the circle, to draw lines and cross imaginary borders. These borders are internal and external. This is why the scenography at times looks like their neighbourhood, while there are hints pointing to a more subtle yet existing violence due to it looking like a segregated space, a prison, almost.

The casual scenes of meetups and exchanges, dances, and fun are interchanged with scenes of discipline, policing, crossing walls, escaping, and being persecuted. When the group disappears and only one or two individuals are left on stage, more intimate relationships are developed, but are soon squashed by internal or external forces. The existing racism, sexism, and poverty that prevail in Morocco and push a part of the population to want to emigrate, including the performers, are poetically pointed out in gentleness and solidarity, making KA-IN a subtly political piece, with a hope of healing the wounds of the world.