CARE as a verb, not only as a noun: what have we been actually practising?

After our previous joint articles on Mentally Safe(r) Spaces and Decoloniality and Questioning Privilege as Embodied Practices, together with the independent researcher Gaia Vimercati, we meet again to generate an inspirational keynote in the frame of the Take Care Conference at CircusDanceFestival 2025. Evidence shows that in circus practice, care is often tied to physical risk, while less visible dangers—emotional, psychological, or systemic—are frequently overlooked, which leaves individuals to navigate them alone. We address the question: Who decides how much care is needed and for whom? This merges the needs of the individual with the collective, where, unfortunately, systemic oppression is rarely considered in discussions on care and mental health, despite the lasting impact of the trauma it creates. Our keynote stresses a pivotal point: without questioning how we organise care, it risks becoming an empty word, disconnected from practice. This reflection invites us to rethink care as an ongoing, collective action—one that involves situatedness, trust, disagreement, failure, accountability, and repair. Just as circus artists must assess risk to support each other physically, cultural workers must develop social consciousness to recognise and address structural pressures. To “take care” should start with the question: What should I know/learn so I can understand better what I should do?

When we think about mental health as a public and collective issue, a specific concept instantly comes to our minds: systemic oppression.

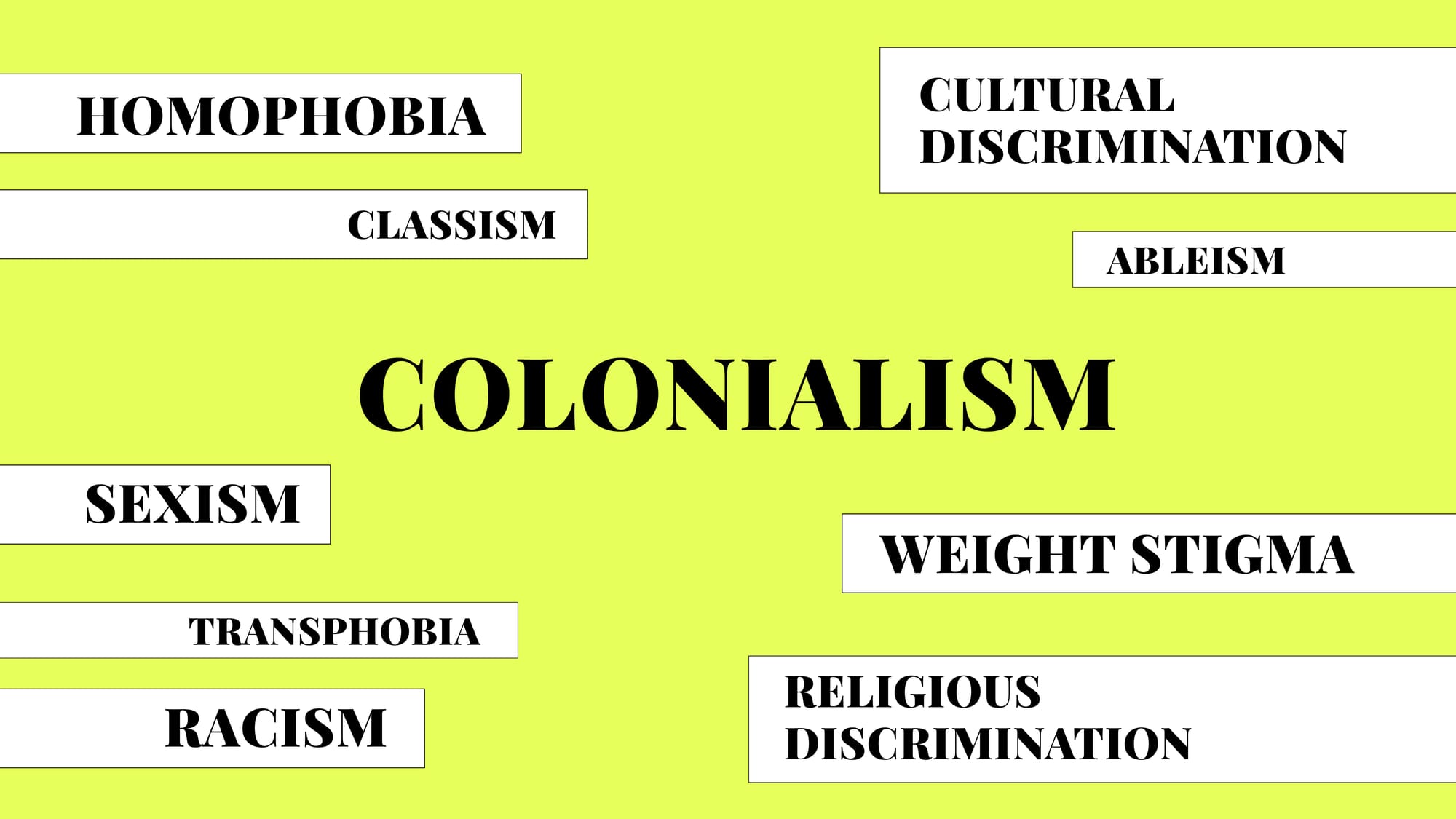

And a long list follows to name it: racism, cultural and religious discrimination, sexism, ableism, classism, weight stigma, homophobia, transphobia and colonialism - and this is definitely non-exhaustive. We feel the need to repeat those words again and again, to INVITE them into the room - not because they are outside, but because they’ve been so invisible in spaces like this (which collaborates to the picture of the society represented in this room today), so a kind of a ritual is needed to welcome the elephants in the room, in the hope that we find our way to heal individuals but also the institutions.

So here it goes: RACISM, CULTURAL DISCRIMINATION, RELIGIOUS DISCRIMINATION, SEXISM, ABLEISM, CLASSISM, WEIGHT STIGMA, HOMOPHOBIA, TRANSPHOBIA AND COLONIALISM.

This ritual is so we can name them whenever needed, open discussions up and allow ourselves to collectively question the oppressive mechanisms that we’ve learnt. Part of their power is the level of fear they provoke in our bodies, that we don’t even dare to say them out loud, and often, don't say them at all.

During this keynote, we’ll mainly look at suffering, which is socially built. We acknowledge the existence of other mental illnesses that are not exclusively connected to social environments, but we believe that even for these, the way that our societies are built around a ‘centre’, considered to be ‘the norm’ adds a lot to the struggle that comes with these marginalised conditions.

So, today we’ll focus on the mental ill health we see growing and growing around us. Conditions which are sadly becoming more common (and the symptoms of which we often romanticise as part of ‘cultural jobs’ or that we tend to endure in the name of improving our careers). These include chronic fatigue, psychological strain and burn-out, anxiety and depression, PTSD, eating and dissociative disorders, all things that might lead to ‘quiet quitting’ as a coping mechanism to stay in the market. We cannot really address the topic of mental health without tackling the structural issues that contribute to creating the ground from which this suffering often arises.

We do believe that a lot of our mental struggles are about the pressure we feel to adapt to a dysfunctional and violent system, and how, while growing old, we are pushed more and more towards a deep submission to the oppressions of so-called ‘society’, taking them as the ‘unchangeable reality’. Still, what we perceive as inevitable is often the outcome of what we have been made to believe is unquestionable. But unquestionability is not an inner quality of the object, but rather an attitude of the subject, and it can be trained and changed.

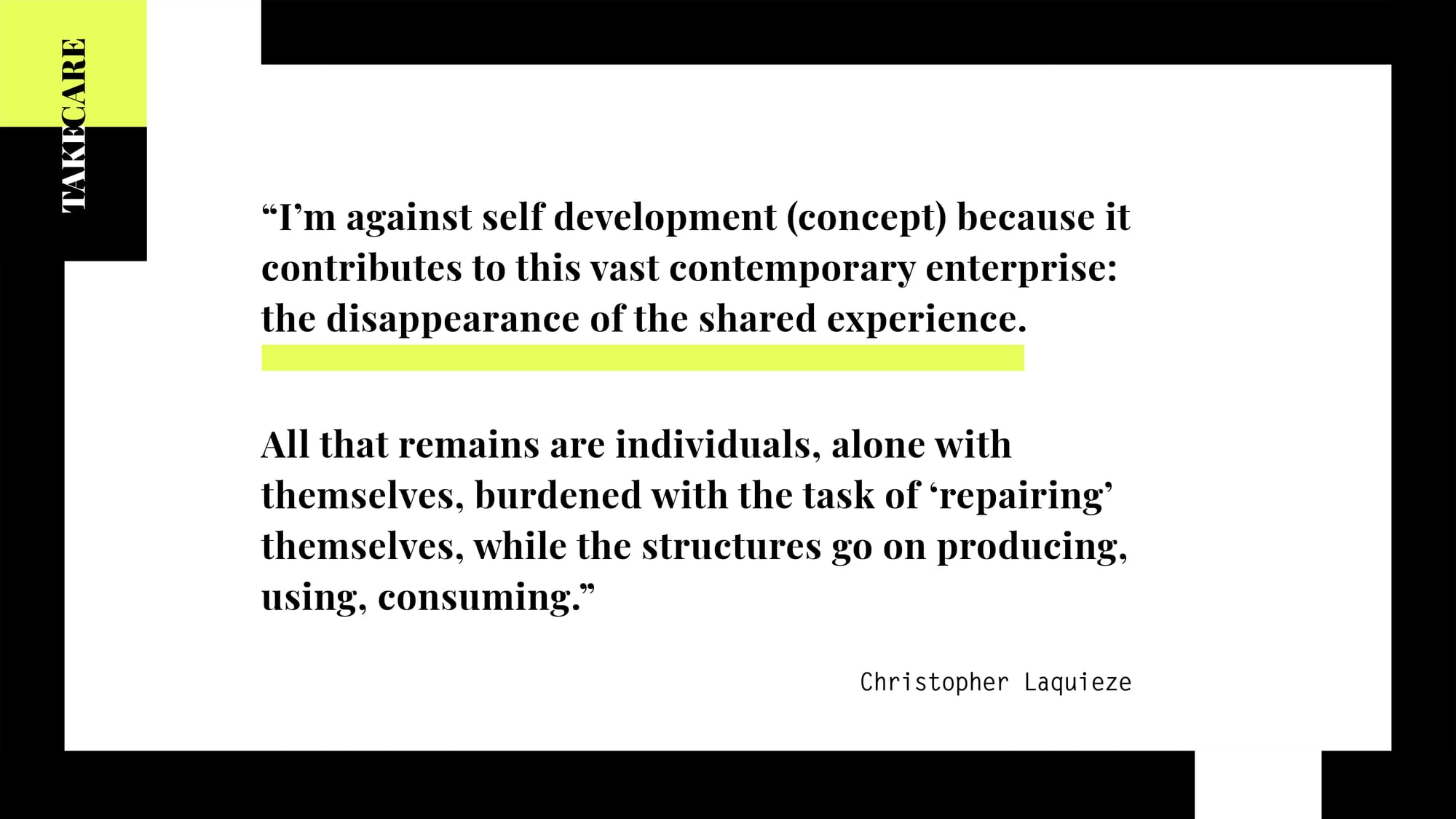

In recent years, the difference between happiness and comfort, between health and calmness, between fulfilment and individual satisfaction has become very blurred. In this context, we should not forget that nowadays the Mental Health topic in Europe is very compatible with the neo-liberal asset and the myth of individual free will. Neoliberalism, as explained by Pierre Dardot and Christian Laval, is a framework that constrains individuals, within which they may feel free and express their desires, but without ever being able to question the framework itself.

Christopher Laquieze wrote, “I’m against it (self-development) because it contributes to this vast contemporary enterprise: the disappearance of the shared experience. All that remains are individuals, alone with themselves, burdened with the task of 'repairing' themselves, while the structures go on producing, using, consuming.”

Even though we truly believe there are many people in the field trying to find a way out or alternatives with the best intentions, we also believe we should be cautious of reproducing systemic oppression. We call them systemic exactly because they don’t rely on intentions (good or bad) to exist; they are the base of our system.

We undoubtedly have to learn more about care practices, about ‘healthier’ (here meaning non-toxic) work relationships and work environments - and of course, this should be not only an individual and informal practice, but work that institutions should take charge of.

However, here the question becomes a bit edgy: how do we make sure that the institution TAKES CARE and not CONTROL of the individual?

The danger we see in institutionalising care nowadays is, again, the slippery slope that late capitalism has created around the meaning of CARE.

For many people and organisations, taking care is often mixed with taking control. Taking care of someone sometimes becomes deciding when they should stop, when they should see someone, how and when they should express their emotions, which emotions are legitimate and which are not, and in which tone the ‘good’ discussions should be had.

So, now that we want to bring it to our professional lives as well, how are we looking at and defining care?

In our opinion, hegemony is the central problem here. Hegemony is one of the most important values that capitalism and colonialism rely on - it’s through making everyone believe we should desire the same lifestyle, have the same models and that every person should replicate it on their own, that those systems keep functioning and growing.

There’s a very thin line between CARE and CONTROL, and most of us have already experienced or witnessed this in our private lives. To take care of someone does not mean making them fit our own models.

So, where should we draw the line between one thing and the other? And how do we do it? Who does it? As anti-racist, queer and feminist movements teach us, limits have to be set in a space where those exposed to the violence can talk and are listened to.

So, when thinking about better practices, are we putting enough energy into making sure that all people involved are invited to the discussion? How are we training ourselves to be able to listen to the discourses of those who experience it from a different standpoint? How are we educating ourselves to better understand our own standpoint when looking at and discussing collective and public issues?

For me, Gaia, to have this space and not to occupy this alone is very important and part of reconsidering the processes of how we draw this line. This goes a long way with care as a verb, as concrete actions we easily understand and can negotiate how to do it, instead of intangible personal intentions.

To be together and yet two voices, not one, in the same room. It can be done.

There is no secret formula other than trying together. Making a continuous effort to create a space that allows for disagreement, keeping in mind that common ground is something that we should work towards every second, and never take for granted.

This keynote is an invitation to walk in the grey area, inside the border, always reminding ourselves of different perspectives - an invitation to see the border as a living space and not one for separation.

This is a place where we try to never forget the danger of finding simple solutions for complex issues. A place where we do our best to find alternatives with the trouble.

And looking for alternatives with the trouble can start by resisting defensiveness against criticism under the guise of “we’re doing our best”, understanding and recognising the importance of complaints as expressions of flaws that have gone unseen for the majority, which you may be part of.

To look for alternatives to things that seem really unchangeable, by resisting passivity or despair.

We believe we should trust our feelings—feelings like discomfort, awkwardness, unease—not as signs of unsuitability or weakness, but as a form of intelligence that subtly informs us of everything we should resist, listen to or at the very least, question.

On top of that, we should never forget that our emotions are informed by our position in society, and therefore, curiosity, social consciousness and listening to marginalised groups’ experience, is crucial to help dismantle the system within ourselves.

To resist a system is to practice accepting critique and feedback not as punishment and with fear, but with gratitude and courage to step back, listen, take a breath, say sorry if needed and work for repair.

However, to be able to stay with the trouble and embrace the grey area, we need to practice COURAGE and BRAVERY. Perhaps, we could use the word moxie.

Moxie to let indignation prevail over resignation.

To paraphrase Guillaume Ouellet, indignation is the first step toward action, a refusal of the absurd. To be indignant is not merely to feel discomfort in the face of injustice and oppression. It is to refuse to let them become the norm and to resist being trapped in cynicism — that dead end which paralyses rather than transforms.

To be indignant is, above all, to reaffirm one’s agency, to reclaim the power to act, and to refuse passivity in the face of a system that infantilises or dehumanises instead of protecting.

The question now should be:

How do we prevent social consciousness from becoming an obstacle to mental health?

How ready are we to rethink the oppressive models we’ve been perpetuating, rather than developing tools to help people fit into those models?

Sometimes healing doesn't look like “peacefulness”. Sometimes it looks like ”honesty”.

And healing spaces are often those that don't lie to you about pain. *

Thank you,

Amanda Homa and Gaia Vimercati

This keynote was presented on June 7, 2025, as part of the Take Care - Circus life in a swing European Conference on Mental Health and Well-being in the Circus and Performing Arts Sector at CircusDanceFestival 2025, Cologne (DE.

Acknowledgments

This keynote was nourished by many thoughts and references that we tried to gather in the list below. Nonetheless, the most important part of the work were the countless amount of hours of discussions about this topic between us and with friends that are also professionals in the field; a one-week residency at Teatringestazione (Naples, Italy) funded by Quattrox4, so we could dig inside to unveil our intimate relationship with the topic and our personal current state of mental health; and most importantly, the experiences we had in our personal lives of being present and supporting real people when the question about mental health required much more than a speech, but immediate actions.

Endless gratitude for all of those who supported us on this writing process in a direct form: Majo Cázares, Mounâ Nemri, Anna Gesualdi, and Giovanni Trono. THANK YOU!

And endless gratitude for all of those who surround us kindly, giving us the support we need every day in our lives, helping us to get going, alive as we can, and ignited as fire.

Articles

Alex Soojung-Kim: “A recompensa do sucesso não é descansar, mas trabalhar ainda mais”, Leonardo Neiva (BR)

Hopepunk: pour une bienveillance radicale, Guillaume Ouellet (FR)

Imposter Syndrome Isn’t a Personal Flaw. It’s a Systemic Issue, Shari Dunn (ENG)

Longstanding Health Crisis In Creative Industries Linked To Passion-Driven Work, Research Find, Matthaios Tsimitakis (ENG)

O esgotamento mental de quem tem vários trabalhos, Ana Elisa Faria (BR)

Thomas Curran: “A sociedade te humilha se você não for bem-sucedido”, Leonardo Neiva (BR)

Radical Care: Survival Strategies for Uncertain Times, Hi‘ilei Julia Kawehipuaakahaopulani Hobart and Tamara Kneese (ENG)

Radical Care: Seeking New and More Possible Meetings in the Shadows of Structural Violence, Kelly Gawel (ENG)

“Nothing comes without its world. Thinking with care” in Matters of Care. Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds (ch. 2), María Puig de la Bellacasa (ENG)

Le "care" : d'une théorie sexiste à un concept politique et féministe, Hélène Combis (FR)

Racism and mental health, Blog (ENG)

Systemic Racism Takes a Toll on BIPOC Mental Health, Nadra Nittle (ENG)

Why We Need Working-Class Cultural Institutions, William Harris, (ENG)

Who is ‘working class’ and why does it matter in the arts?, Lanre Bakare and Nadia Khomami (ENG)

Books

When I dare to be powerful, Audre Lorde (ENG)

Decolonizzare lo sguardo, Grace Fainelli (IT)

On connection, Kae Tempest (ENG)

The Feminist Killjoy, Sarah Ahmed (ENG)

Staying With the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Donna Haraway (ENG)

The New Way of the World: On Neoliberal Society, Pierre Dardot and Christian Laval (ENG)

Podcasts and videos

Moral Injury and the Ethics of Care, Carol Gilligan (ENG)

Organisation du travail dans le spectacle vivant: quelle éthique du “care”?, rencontre SACD - Artcena (FR)

O cuidado: teorias e práticas, Helena Hirata, Bárbara Castro e Liliana Segnini (BR)

We know inequalities matter and have a huge impact on mental health, why are we so bad at doing something about it?, Panel discussion from the ESRC Centre for Society and Mental Health Conference (London, 1st October 2024) (ENG)

'Why I'm no longer talking to white people about race' – podcast, Reni Eddo-Lodge (Article version here) (ENG)

L'outil le plus vicieux du néo-libéralisme, Matthieu Bellahsen / France Culture (FR)

To know more about the Take Care Conference, read the introduction article by Valentina Barone and the keynote Circus & Science: An Overview of Health Research and Monitoring in Circus Performance by Rogier van Rijn.