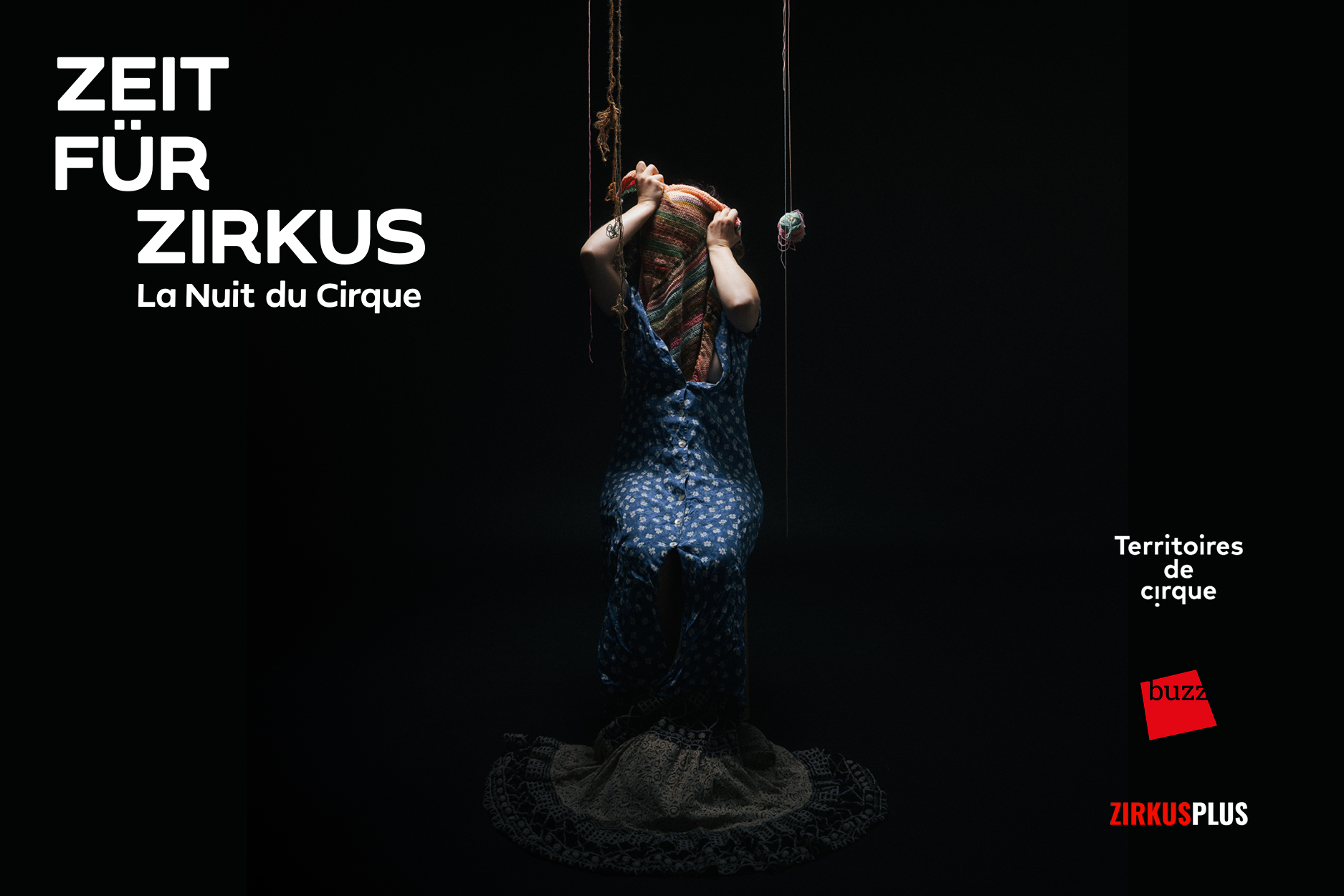

Pamela Banchetti’s Forget Me: A Thread Without Hold

In the frame of the Zeit für Zirkus days in Cologne, at the CCCC, a body tells what words cannot.

Forget Me begins with a stark contrast. The reception is loving: Pamela Banchetti greets the audience at the door in several languages, warm, almost caring. But as we move into the cramped space, the air thickens, the light darkens – care flips into insecurity, closeness into constriction. In this dense atmosphere, even the softly crocheted landscape does not appear as a cosy environment but rather as part of a claustrophobic setting. Contemporary circus is far removed from joy and flaming hoops – instead, a raw drumroll descending into dark narratives.

Forget Me is a fairy tale – but not one that soothes. Fairy tales usually take place “a long time ago” or “in a faraway land.” Yet the genocide in Gaza is neither “a long time ago” – rather for a long time – nor in “a faraway land.” And above all: it is not a fairy tale. But precisely in this lies the bitter punchline. The performance is inspired by We Are Not Numbers by Ahmed Alnaouq and Pam Bailey – a book in which young people from Gaza describe their realities, as a counter-narrative to the ironed-out stories of international reporting. Banchetti opens exactly this fissure: between the fairy tales we are sold and the reality that so often goes unheard. This contrast is noticeable in the stage design as well: small hanging wool tufts on the wall promise a Christmas story beneath the fir tree, yet the performance reveals itself as a dark scenario à la E.T.A. Hoffmann, in which the boundaries between fantasy and reality are deliberately blurred. The host, now enveloped in a crocheted hooded coat, appears as a frightening warden bringing light into the dark, even though she cannot illuminate the story; she laments a lack of strength to enable the transition between our worlds. And perhaps there lies another truth: such transitions – especially with regard to Gaza – cannot easily succeed. They often seem impossible, avoided out of overwhelm or fear. But they must be made. And indeed, we set off into a foggy soundscape between nightmare and 90s run-and-hide game.

The adventure thus begins without a hero figure; the human being is too weak for human catastrophes. Instead, a frog acts as a mediating instance: where once there was a mouth, two bulging eyes suddenly shoot out. It leads us to a grandmother. But can she be trusted? Or has the wolf, as in Grimm’s fairy tale, thrown the knitted coat over himself? One wants to ask: Grandmother, why are you wearing an apron? Apparently, to bake a cake – one made of body and soul: arms wrung out, pores squeezed, imaginary entrails pressed from the vulva. Everything wanders into the mysterious dough. It is the physical moments in which the piece becomes strongest: when Banchetti tells with her body instead of merely using it.

A highlight: the landscape awakens. The crocheted stage, previously scenery, becomes a living being. Banchetti disappears beneath it, fingers poking through stitches, feet protruding. Where the piece previously risks losing itself in its own absurdity, a sensual, clear image emerges: fantasy burrowing its way outward. Later, she crochets a long thread live – one you almost want to cling to in hopes of finding hold in this world. But it doesn’t succeed; perhaps it is not meant to succeed; perhaps the audience is meant to get entangled, caught in the crochet net. And suddenly, the grandmother breaks out: with impressive playfulness, Banchetti throws herself into the character, screams, improvises, mutates. Every boundary of shame falls. Yet this intensity finds no counterpart. The performance remains trapped in its own world, without cut, without opening. This feels less heartbreaking than alienating. The room grows heavy, the atmosphere oppressive. Some in the audience read in it the tragedy of an estranged grandmother losing herself – a psychological exceptional state culminating in a scream. Others think of the voices of the young people from Gaza, so often left unheard.

The frog leads back to reality, where the outcry sometimes wants to remain unheard on purpose. Like a matryoshka, the figures slide back into one another. After the outburst, Banchetti asks the question many are likely asking themselves: What was the point of that? A disarmingly honest question. The warden doubts herself again, wants to crumble her identity into nothingness: “I’ll help you to forget me.” Rarely has a sentence sounded so cruel and so tender at once. In the end, once again, a hard shift in tone: in the final applause, the friendly host returns and has baked a cake. Grandmother’s recipe remains a secret – like so much in this world of wool, fantasy, and unfinished transformation.

This article is part of the German project ZirkusBlog, which took place during the Zeit für Zirkus 2025 edition in Cologne. The coverage of Zeit für Zirkus - Zeit zum Reden, organised by the BUZZ - Federal Association of Contemporary Circus, is sponsored by the Performing Arts Fund and the Cultural Office of the City of Cologne. The original German texts were published on ZirkusPlus and on the festival website.

Read more on Zeit für Zirkus 2025 in Cologne

Zeit für Zirkus Cologne 2025: a contemporary scene in the making

Ready, Set, Juggle: Hippana Maleta’s Runners at Schauspiel Köln

Time to Talk [about] Circus in Cologne: Matchmaking and cold feet

RAPT: a piece of paper for observant minds and thoughtful gazes

High (on) Fashion: In the frenzy of the fashion industry

ANGELS Aerials: How Not to Forget How to Fly