On Contemporary Big Top Circus: Insights from Collectif Malunés and Cirque Rasposo

The 2025 edition of Theater op de Markt welcomed two reflection days under the title ON CIRCUS. Initiated in 2023, in collaboration with Hanna Mampuys and Toon Van Gramberen of THERE THERE Company, the format invited circus companies to step away from the stage and into conversation. Each session unfolded over two hours, with the two authors each day having 30 minutes dedicated to sharing a presentation, followed by an open discussion bringing artists and professionals into the exchange. ON CIRCUS 2025 took the shape of two morning conferences, welcoming four circus authors and unfolding around two distinct thematic focuses.

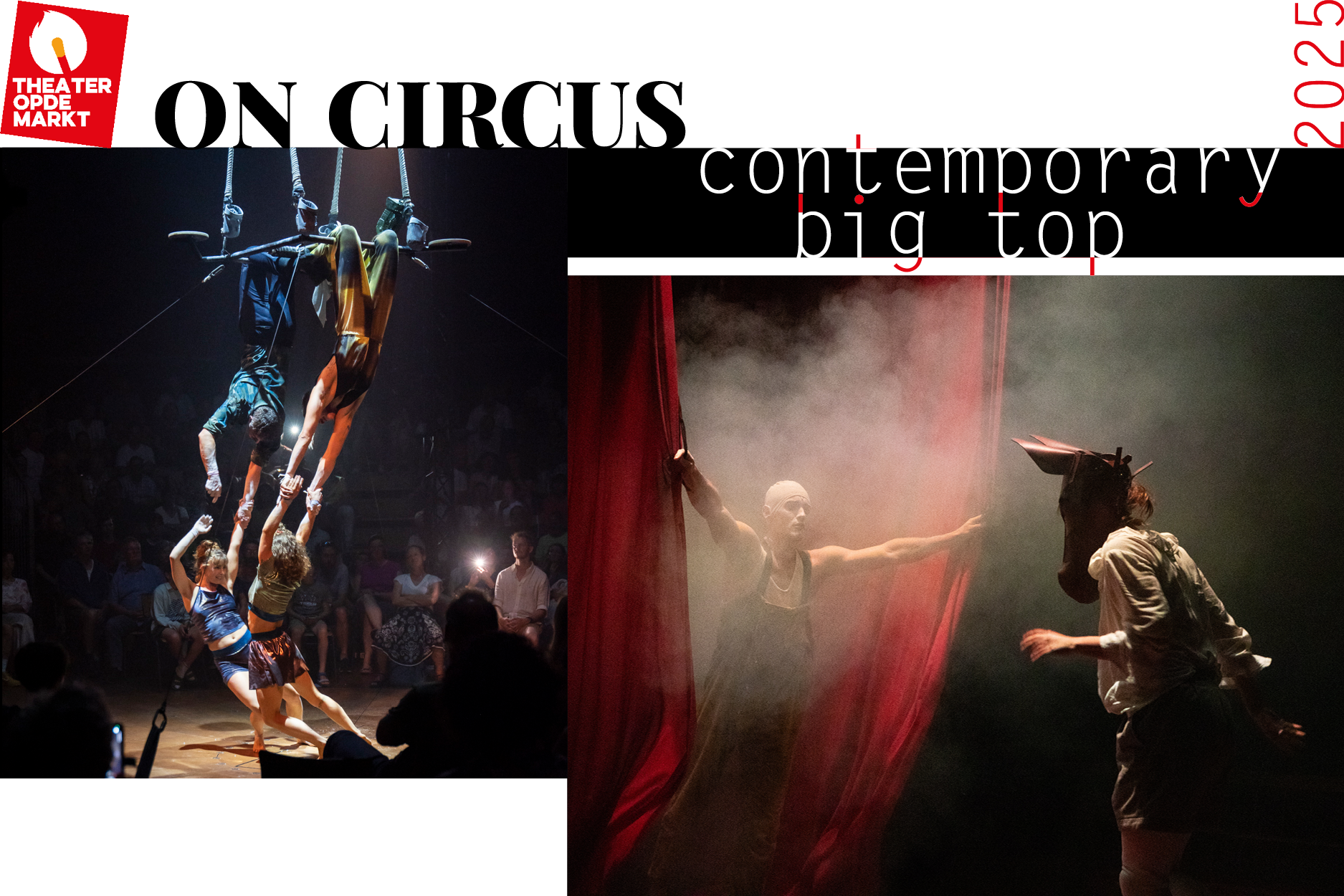

The first day, On Contemporary Big Top Circus, drew on knowledge and experience from several creations by the Flemish Collectif Malunés and the French Cirque Rasposo. With Simon Bruyninckx and Marie Molliens representing each company, we were invited behind the scenes to explore their artistic processes, motivations, and working realities as they reflected on their latest productions, Tout va Hyper Bien and Hourvari, both presented at Theater op de Markt 2025.

A transient place, a temporary home, a nomadic circular structure—why does it remain, even today, such a powerful and reliable venue? “If you love it, you choose it,” every big-top owner seems to imply. Both fragile and strong, it stands still in its freedom on borrowed land. A big top is therefore not just a technical choice, but a commitment to a way of working and living. Even nowadays, as a sort of post-humanist entity, a big top is treated as a living thing. Regular checks on the weather, structure and other necessities are essential. It demands intention, specific knowledge, skills, and constant maintenance.

I find it interesting that the circus, in its nomadic form, brings with it a symbiotic way of living. Perhaps, the circus's lifestyle common thread linking traditional and contemporary might also be traced in the relationship with otherness and the community life of a group of people with animals and apparatuses, that interrelates its members and often sees them working together to take care of each other.

Through this lens, two contemporary lifestyles emerge side by side. Simon Bruyninckx speaks of founding Collectif Malunés as a collective that functions like an extended family. Meanwhile, Marie Molliens, with Cirque Rasposo, has taken up her parents’ artistic legacy, reshaping it into a family built around her own vision and authorship.

Collectif Malunés: Where Circus Roots Meet Immersive Worlds

After the ritual welcome by Martine, Hanna, and Toon, the Flemish circus artist Simon Bruyninckx takes the floor. He guides us through Collectif Malunés’ journey with the big top—its challenges, its necessities, and its enduring pull.

As many of you already know, the collectives’ members decided to form the company while still studying at ACaPA, Tilburg. They shared values and the dream of buying a big top. Guided by a fascination with the art itself, it was mostly Vincent who was convinced about the choice of a big top. Attracted by the lifestyle of Circus Ronaldo since he was young, he became a close friend of the company and imagined a similar future. His fascination continued while he studied in France, a country more familiar with circus tents and nomadic life. Collectif Malunés created their first street show, Sens Dessus Dessus, during the summer break and started touring in their free time. They decided not to pay themselves, but rather to think ahead and finance their future circus tent.

The collective lives together during tours but is also aware of the importance of taking long breaks. They avoid copying the never-ending tours of traditional circus companies with a tent. Mental health awareness and good working conditions in the circus sector are improving. The new generation of artists is more aware of the need to preserve themselves and prevent burnout, rather than consuming all their physical and mental resources.

Another pivotal difference between traditional and contemporary use of a big top is administrative management. Collectif Malunés does not sell its tickets directly. Like many other companies, it works with partners to cover costs. Meanwhile, the organiser hosts their caravans and tents for consecutive days and handles the marketing. Touring under a big tent also requires including build-up and break-down days as part of the process.

Living as a family of seven is beautiful but also challenging, especially during the creation process. The horizontality of decision-making becomes a “killing the ego” practice. Collectif Malunés embraces the “we agree to disagree” principle. Every voice counts and needs to be heard in the process of building common trust and making final decisions.

Not all creations are the same, and none are alike. Simon explains that, even though their horizontal method of writing and collective decision-making is well-established, each experience is new and full of unknowns. Compared to the “pink cloud” atmosphere that characterised the process of We agree to disagree, they had a more challenging creation with Tout va hyper bien. However, the final result makes up for the perceived lack of harmony within the group during the process. What matters, and what remains, is the quality of the human relationships within the collective.

But what are the benefits of owning a big top? Simon highlights the positive aspects of this artistic choice. The arrival and presence of a big top in a city is quite visible, and often, the kind of audience involved is far from being just middle-class white people.

Performing under the big top also means consciously giving up the use of frontal adaptations in a theatre. Embracing the circular space and the slowness of a circus tent is rewarding. It gives time and freedom to assemble its parts as desired. It is like inviting people into your own house. You can adjust the settings, reconfigure the scenography, and adapt the space to each creation. And, after the show or in collaboration with the festival you’re working with, you can host parties and side events that embrace the big top’s fundamental conviviality.

For Tout Va Hyper Bien, they redesigned the seats, built a musician’s stage, and added new balconies. These scenographic changes foster a sense of belonging to the structure while maintaining the excitement of discovery that drives artistic creation. Vincent particularly values the circular structure, which allows people a sense of equality and invites them to position themselves in the space. In this atmosphere, a performer cannot hide anything from the spectators. This constraint paradoxically frees the need to be humble and underlines the necessity of creating what he calls “honest circus.”

As the French circus author Johan Le Guillerm reminds us, adopting a singular, unique point of view is part of the magic of experiencing a show under the big top. What could be more innovative than turning the two dimensions that define the arena and the stands upside down? In Tout Va Hyper Bien, after a long welcome gathering with the bar open and chairs and tables positioned at the centre of the arena, the spectator’s position is constantly suggested to be moving. The show is the next step in Collectif Malunés’s collaboration with dramaturg Cathy Lever, who also contributed to We agree to disagree, introducing what is called “porous dramaturgy”—a method that, here, brings immersive theatre into circus.

Over time, Collectif Malunés has learned to amplify its greatest strength: communicating with the audience. Previously, they deconstructed the big top to perform outdoors, creating a distinctive way of interacting with spectators. In Tout va Hyper Bien, engagement extends even further into the spatial scenography, which is constantly reconfigured by each spectator individually and as part of the collective audience, moving with and around one another. You begin the show on one side of the tent and end on the opposite side. Living under Collectif Malunés’ world for 90 minutes is enthusiastically demanding. The audience is invited to physically engage. Cooperation between strangers is a joy to witness—a reminder that we can be together, for real.

You might converse with a trapeze artist flying over tables, make space for transforming tables into a unique sea for iron-jaw surfers, define the perimeter of a Cyr wheel act, or witness a single spectator’s involvement with the music band. You often actively choose where to sit or stand, shaping your own perspective and the development of the performance. Layer by layer, your engagement evolves. You move from relaxed observation to ensuring that scenes unfold safely, while also feeling freer to move and participate alongside others. I remember thinking, “This is queerness at its highest potential, realised through the form of circus.” And, unexpectedly, I felt hopeful again.

Cirque Rasposo: The Ancestral Power of Circus and the Big Top as a Mental Space

Introduced by Hanna Mampuys, the floor is handed to the French director Marie Molliens, artistic director of Cirque Rasposo, the second guest of ON CIRCUS’s 2025 first day, focused on the theme of the contemporary big top.

When I think of Cirque Rasposo, the word that first comes to mind is imaginary. Their aesthetic evokes a hypnotic surrender, asking audiences to embrace the performance before fully understanding it. Each show requires a willingness to feel, to consent viscerally to the world that is revealed beneath the big top. Cie Rasposo creates an immediate immersion: stepping under the tent is stepping into a reality governed by different rules and rhythms. For Marie Molliens, the circus space is foremost a place to touch the audience on a visceral, almost instinctual level.

She calls this reaction “the nerve impulse” because it is the body that responds first. Using the big top as her instrument, Marie makes this impulse visible, constantly asking how the spectator will experience it from within the tent. The company’s aesthetic draws on its own inspirations, blending an archaic, embodied vision of circus with reflections on human behaviour and contemporary social issues, all while weaving its own unique narratives.

Marie’s artistic work emerges as a space where her vision grows in dialogue with both her experience as an artist and as a woman, constantly engaging with the modern world. Cirque Rasposo approaches circus distinctly and unconventionally, and its aesthetic identity is immediately recognisable.

Cirque Rasposo's creations draw on an aesthetic steeped in the past. Set designs and costumes evoke centuries gone by, while resonating with the issues that preoccupy us today. In particular, the company’s two most recent works engage directly with the values shaken by the recent pandemic. When is individual freedom endangered, and when is risk necessary to fuel one's critical spirit? What can be preserved—and allowed to breathe—within a society homogenised by the imperative to consume and to regulate perceived danger?

Marie Molliens takes imagination seriously, and in this context, the use of a big top amplifies Rasposo’s singular appeal. For her latest creation, Hourvari, the big top’s entrance is framed by the gaping mouth of a monstrous fish. We are all invited to step inside the body of a mythological creature to explore questions that concern us all.

This singularity reflects a metamodern reinterpretation of traditional circus values, as well as the high technical standards associated with its most rigorous forms. The embodied mode of reception and the unique pact formed through the proximity of performers and audience are the central entry point to Cirque Rasposo’s understanding of the big top as a mental and emotional space.

Cirque Rasposo is almost 40 years old, and was founded by Marie’s parents, indoor theatre artists who later chose to become street theatre performers. For nearly 20 years, the company operated first as a street theatre troupe and then as a street circus, with Marie and her brother and sister participating in their parents’ shows from a very young age.

Marie completed her training as a circus artist at the Fratellini school in Paris. The company then invested in its first big top, a small, traditional tent, to stage what would be the first of many shows under a circus roof. As a wire-walker, performing outdoors had been challenging for her, while the protected space of a big top offered a welcome relief.

It also allowed her to feel fully in tune with the technical aspects of circus. Theatres are rarely adapted to circus realities: setting up a wire in a theatre is often extremely complicated, whereas in a big top, everything was theirs, and every circus discipline was finally welcomed. Rasposo is now on its seventh creation, and Marie assumed the role of leader after her mother, making her debut as artistic director in 2013 with the show Morsure.

From the technicalities to the lifestyle, Marie underlines that living with an itinerant big top and in caravans allows you to bring “all that you need, and is not possible to bring with you in a hotel.” The choice of a big top is suitable for living with your own extended reality. Marie’s mother always travels with the company, as do her children and domestic animals.

A consequence of an itinerant life is the development of a different way of perceiving human relationships: living in a camp like a small village, self-management naturally comes into play while sharing a circus life. This aspect feels very archaic. In her words, they seem like Native Americans: they live in a tribe, pitch a tent, have animals, and fetch water from the fountain.

This way of life inevitably shapes not only how the company travels, but also how it creates. Rasposo does not function as a collective; they are first and foremost a family unit with a kind of lineage: first Marie’s parents, and now Marie with her partner and children. Around this core, there is a close circle of people who have been involved with the company for about fifteen years, and depending on each production, different artists join this group for extended periods.

Casting for Cirque Rasposo is always a delicate, lengthy, and crucial process. Since time on tour is extensive, compatibility with living nomadically for three or four years is essential. They conduct carte blanches and residencies to test whether artists can work and live together, and once a team is formed, it is usually because they have chosen carefully.

These human and temporal constraints find their most concrete expression in the spatial choices of the big top. Marie’s way of experimenting with circus languages starts with the fascination of a specific discipline, integrating each aesthetic and artistic choice into the way the big top is used.

To support each scenographic effect, the big top’s dimensions, shape and internal configuration are carefully considered before each artistic creation. In a big top, the audience can sit underneath, around and even above, creating a multitude of perspectives. These spatial possibilities are largely absent in theatres, where the perspective is usually frontal.

Proximity is essential, and Cirque Rasposo works with relatively small big tops to reinforce this intensity. For her second show as artistic director, La DévORée, there was a bullfighting dimension: she created a tiered seating area in the shape of an arena. The following creation, Oraison, was more intimate, with a mystical quest: the big top became a kind of oratory, a chapel.

For Hourvari, the internal configuration has changed again: the audience is positioned on two front sides. The show’s big top is 25 years old, very light to set up, and still features cornices like traditional tents. Usually, the lighting bridges that cross a big top can denature the space, so they chose instead to place small spotlights attached here and there, taking advantage of the cornices.

The stage is a long horizontal line framed by red draped curtains. Combined with the bifrontal view and the teeterboard discipline, the space is used to focus your attention vertically. Circus techniques usually performed in a larger setting are now executed in a reduced space. This scenographical choice creates a zoom effect, similar to a close-up in film. The show carries a ritual, transformative energy that contains and guides the audience along the dark path of a fairy tale, scenographically enacted as the act of passing under the canvas to enter immediately after the prologue, before taking a seat.

In Hourvari, multiple actions unfold simultaneously, drawing your attention from one character to another. Time feels suspended. You know you are witnessing a fictional event, yet it feels strikingly real—surreal and powerful, like a fairy tale in motion. Chaos and order are questioned, balanced, and played as two sides of the same coin, a conceptual duel echoed in the use of the bifrontal tribunes. Surrender, and inhabit your mental space. All around you, it is Cirque Rasposo, feeding your imagination under their big top.