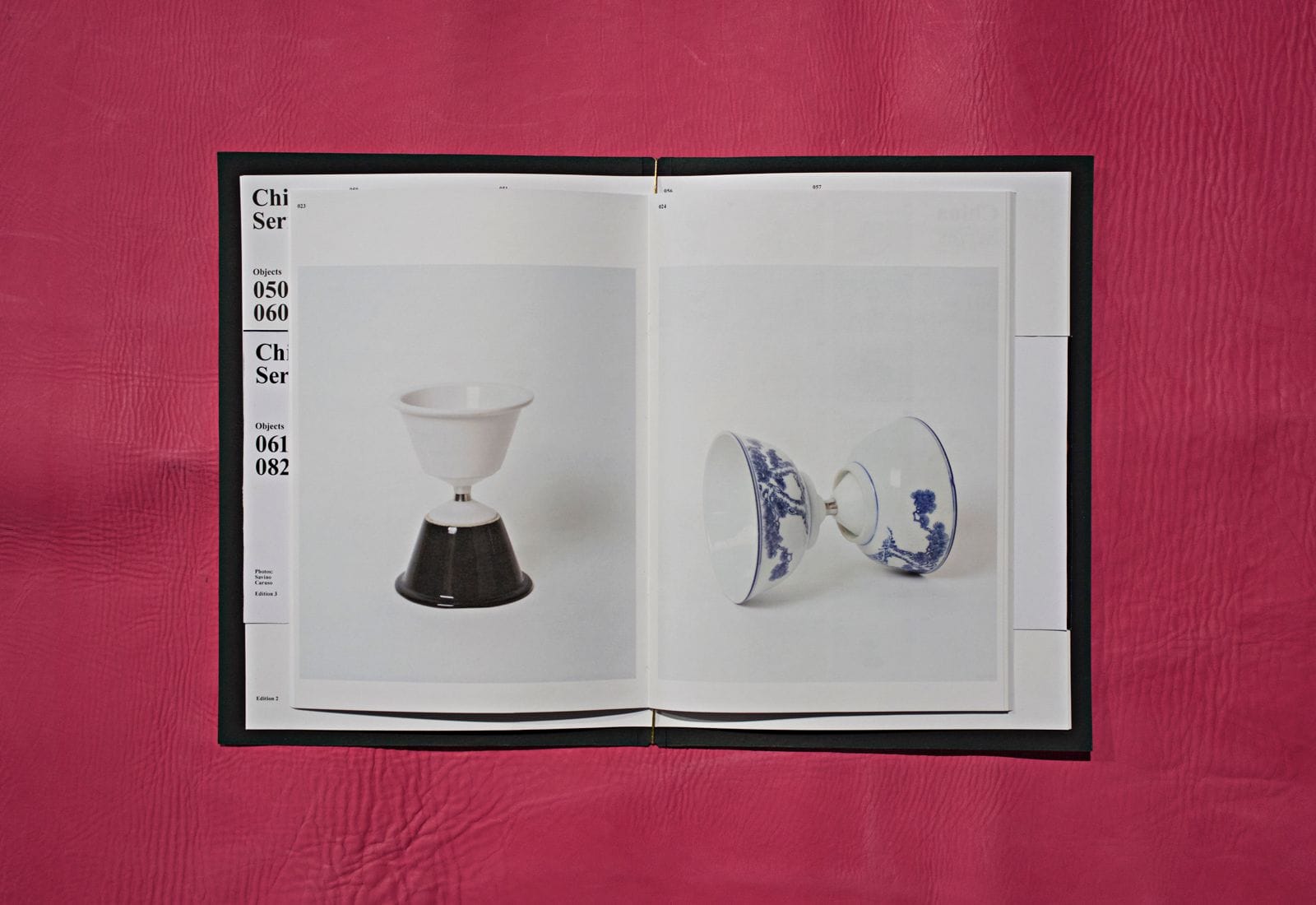

On Circus Scenography: Reflections with Julian Vogel and Boris Gibé

The 2025 edition of Theater op de Markt welcomed two reflection days under the title ON CIRCUS. Initiated in 2023 in collaboration with Hanna Mampuys and Toon Van Gramberen of THERE THERE Company, the format invited circus companies to step away from the stage and into conversation. Each session unfolded over two hours: each of the two authors per day had 30 minutes dedicated to sharing a presentation, followed by an open discussion, bringing artists and professionals into the exchange.

The second day, ON Circus Scenography brought together the interventions of Julian Vogel - Cie unlisted and Boris Gibé - Les Choses de Rien, whose work engages deeply with plastic arts, visual composition, and scenography in circus.

In contemporary circus, where interdependence and non-anthropocentric perspectives are central, objects are rarely mere things: props become partners, and scenography is seldom reduced to decoration. Material elements act as counterparts, illusion-makers, and sometimes even as agents within the performance.

Within the international contemporary circus landscape, Julian Vogel and Boris Gibé stand out as two authors whose work demonstrates a particularly distinctive engagement with objects and scenography. While both place materiality at the heart of their artistic language, their relationships to objects diverge significantly. Their approaches reveal two different philosophies of scenography, creating a tension that opens up a rich field of reflection on what scenography can be—and do—within contemporary circus.

Objects in Dialogue: Materiality, Attachment, and Scenography in Julian Vogel’s Work

The morning started with the intervention of Swiss artist Julian Vogel (circusnext laureate 2020-21), who offered a panoramic view of his circus research. Julian explores the potential of circus objects, often merging their performative dimensions with plastic and visual arts. His creative journey began as a student and evolved through a sustained curiosity around the arts, alongside a persistent interest in deconstructing the performative aspect of diabolo technique to open up new staging possibilities.

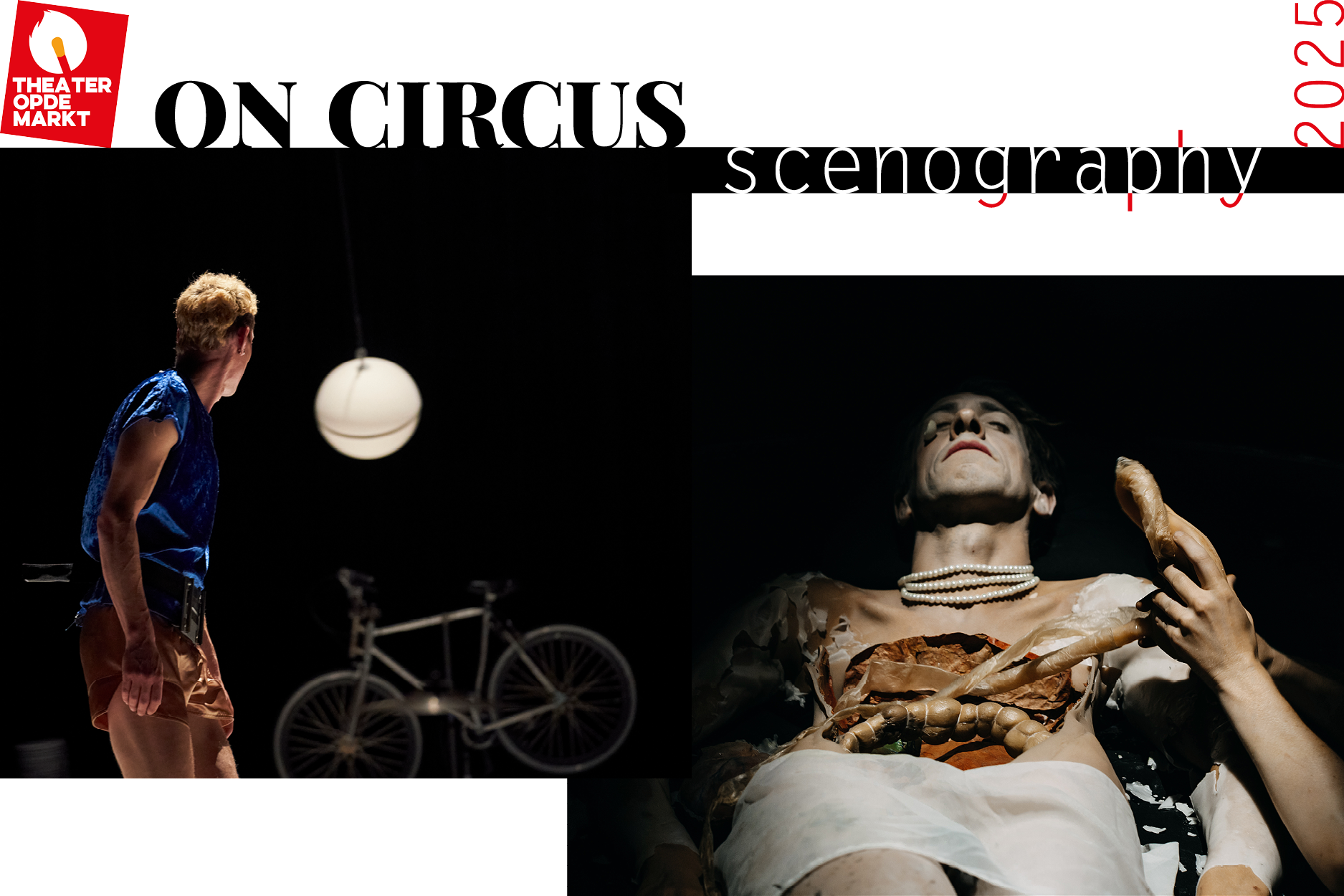

The material consequence of this operation is the creation of China Series, his first exhibition-performance, in which the diabolo is constructed from ceramic components, reassembled and recomposed in variants, often motorised. This research later evolved into Ceramic Circus, the show he is currently touring and presenting at Theater op de Markt 2025.

As Julian emphasises, the core of his work is using and playing with “a lot of stuff”, which invariably turns out to be “not just stuff”. He describes his relationship with objects as ambivalent and invites us behind the scenes to reveal how this relationship has developed over time.

Through his talk, we gain insight into what objects represent for him: their meanings, their visible and invisible qualities, and which aspects of their materiality are essential for a performance. This exploration allows us to understand how they arrive on stage, through long and often invisible processes of creation that evolve behind the scenes.

Julian’s meeting point with the object as a scenographic experimental element begins with his discipline: the diabolo, a singular apparatus composed of two symmetrical halves, resembling inverted bowls, designed to spin and be manipulated through juggling.

It was the object itself that suggested building it from fragile, everyday ceramic. He began frequenting second-hand shops, assembling every ceramic diabolo that shared the same basic features but differed in components, shapes, colours, and sizes. Acquiring “a lot of stuff” opened up a vast universe of creative possibilities.

Once these objects were in his hands, training became difficult due to the constant fear of smashing them. The apparatus, now understood as a work of art, acquires a fragile existence that can be interrupted through use. This attachment to fragile ceramic diabolos, combined with the instinct to protect them from breaking, ultimately led him to develop a circus project that bridges installation and performance.

China Series emerged as a constellation of works centred around these objects. Shape and fragility became core concepts, accompanied by practical questions: how can these fragile objects be manipulated? How can he influence them? And conversely, how can they influence him? These questions led him to explore forms of representation that may or may not involve his physical presence. As a cross-disciplinary work, the interaction between artist and object remains open-ended, with each installative performance catalogued sequentially, one after another.

During his studies at ACaPA in Tilburg, Julian gained access to the art department’s ceramics kiln and became interested in firing clay himself. He later also did a residency at the EKWC - European Ceramic Work Centre to continue this practice. Being able to reproduce diabolos independently liberated him from the limitations imposed by finite objects. His diabolos needed to be more numerous than their actual use. Ultimately, objects matter because of their meaning: even when smashed, they are not merely consumed.

The invisible labour in Julian's ceramic work is precisely in this backstage process, shaped by time, manual effort, and the variables required to construct the objects that later meet an audience. One of his most recent creations, the installation Crescendo, exemplifies this dimension: an imposing metal structure connected to one hundred ceramic tubes, requiring weeks to build. Working on this structure pushed his physical, mental, and emotional limits.

The theme of reproducibility recurs in Ceramic Circus, in which the ceramic sphere suspended from a wire on stage is produced in as many copies as required by the artist.Julian also designs the plates he spins and deliberately breaks. At every show, it is unpredictable how many he’ll let fall, and because of that, their production involves collaboration with a French company that both manufactures and recycles them.

Ceramic Circus maintains ceramics as the central leitmotif of Julian’s research, while introducing new objects that reflect his evolving interests and new passion: a drum, an inverted bicycle, spinning ceramic plates, and roller skates. He always finds learning new skills exciting. Currently, he has begun a project that blends knife-throwing techniques with the art of crafting porcelain knives, and he is also intrigued by creating clothing from broken porcelain pieces. His artistic trajectory continues to expand the dialogue between object, performer and performance.

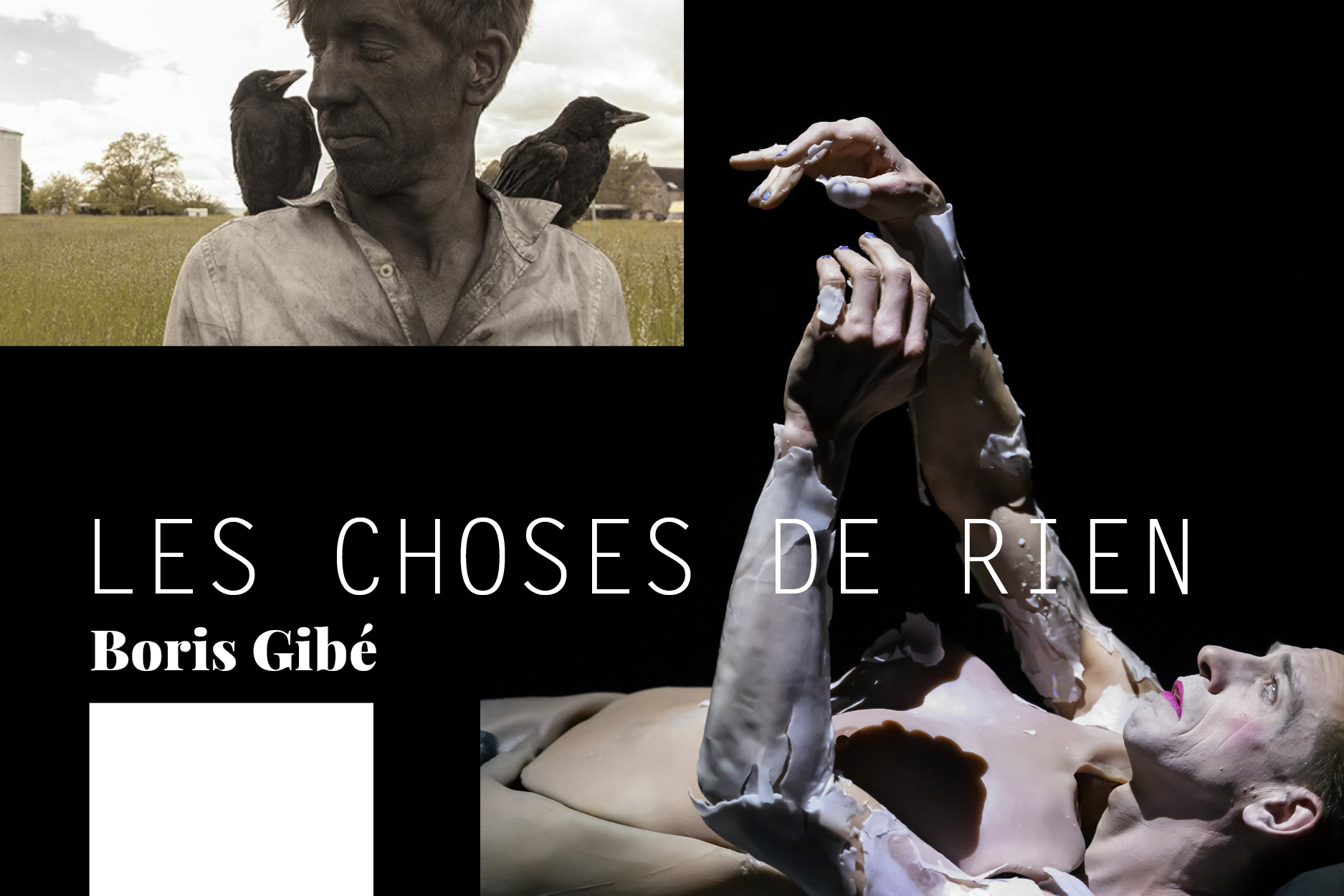

The Artisan of Reality: Boris Gibé’s Porous Canvas and Immersive Scenic Spaces

Following Julian's intervention, the session continued with the French creator, Boris Gibé, a multifaceted and innovative circus artist who has forged a singular artistic path. Renowned for his integration of moving images and his in-depth exploration of scenic elements, he approaches the stage as a space of experimentation and reflection.

His artistic journey began in adolescence, when he first encountered circus and dance as leisure activities. These early experiences led him to perform in commercial settings such as supermarkets, birthday parties, campsites, and village fairs. At the age of twenty, Boris founded his own company, Les Choses de Rien, marking a pivotal moment in his career. This decision reflected his desire to move beyond the conception of circus as mere entertainment. He sought to challenge the expectation that circus must always be humorous or light-hearted.

For Boris, the circus offered a form of social legitimacy: a way to exist in the world while affirming his difference and individuality. Circus became a space of acceptance, a parallel reality distinct from conventional social structures. It functioned as a refuge from the world, enabling him to consciously distance himself. He views circus practice as profoundly transformative for those who engage in it. Each new creation, discipline, apparatus, or collaborative relationship reshapes the artist’s perspective.

Changes in performance spaces similarly influence this evolution. Much like how behaviour adapts depending on social context, circus artists reveal different facets of themselves depending on their environment and interactions. Boris also reflects on identity as a determining factor in how individuals form communities. He understands identity not only in relation to others, but also through one’s relationship with objects—objects of desire, tools of interaction, and mediators of social exchange.

Questioning the limits of the genre, he asked why circus couldn’t be like cinema; he believed that circus possessed the capacity to evoke a wide emotional spectrum and wanted to encourage audiences to engage with these varied sensations. This inquiry became a driving force in his exploration of new circus aesthetics. It led him to constantly reassess his own practice, guided by an ongoing search for meaningful and emotional forms that express themselves through immersive stages and detailed object scenography.

Cinema—particularly the films of Andrei Tarkovsky (Stalker, The Sacrifice, The Mirror)—has been a major influence on Boris’s work, especially in his creation, settled into a silo, L’Absolu. Tarkovsky’s reflections on artistic responsibility and the pursuit of truth, articulated in his book Sculpting in Time, strongly resonate with Boris’s own artistic concerns.

Boris loves to create immersive scenic spaces that audiences can physically enter. He values the artisanal approach, striving to balance practical challenges with the artistic reality, always aiming for the audience to experience to be destabilising and akin to vertigo. He leads them to question their certainties, the conventions of representation, and to construct new perspectives. He embraces and invites you to embrace the dual reality of circus—being both grounded in technical and practical work, and open to infinite imagination—finding value in the balance between the two.

To him, circus constitutes a parallel world in which artists assume complete responsibility, from production to communication. Learning a discipline such as juggling teaches acceptance of failure, with dropping objects being intrinsic to the process. Even the relationship with the audience may falter, yet circus embraces impermanence: shows under a big top can be dismantled and reassembled elsewhere.

This transience aligns with Boris’s notion of the “porous canvas”, a space not bound by rigid conventions. In this sense, the circus author becomes an artisan of reality and of relationships, inviting spectators into an experience they may not fully anticipate. Integrating the audience into this porous space is central to his artistic vision.

The construction of the silo for L’Absolu exemplifies this approach. It was built over two years with the help of approximately twenty volunteers. At the beginning, Boris personally handled sound and lighting, allowing him to experiment freely, reconnect with his initial intentions, and evaluate the work from a broader perspective.

His creative process does not begin with a fixed narrative or scenography. Instead, he gathers a collection of spaces, ideas, and sensations that intrigue him, then searches for a visceral and introspective question to explore. His work often emerges from uncertainty; once understanding is reached, he moves on to new enigmas.

Works such as L’Absolu and Anatomie du Désir investigate the circularity of circus and the dynamics of observation. In these performances, spectators and performers are simultaneously observers and observed, and the exchange of gazes becomes a central theme. Boris is particularly drawn to the “magic box” of the overhead view, which encapsulates both the power and mystery of circus. This vertical perspective conceals technique while blending sound, light, and machinery into a sensory experience that prioritises sensation over comprehension.

He notes that jugglers often adopt a strongly visual approach, focusing on multiplying and questioning objects, whereas other circus disciplines may lean toward social interaction. Influenced by artistic movements that expand the notion of the object—such as Jeanne Mordoj’s L’Éloge du Poil—Boris values the diversification of objects and the creative possibilities they generate.

Each new creation introduces new objects and staging techniques. In Les Fuyantes, for instance, the scenography itself became a circus apparatus, incorporating elastic walls and intricate pulley systems.

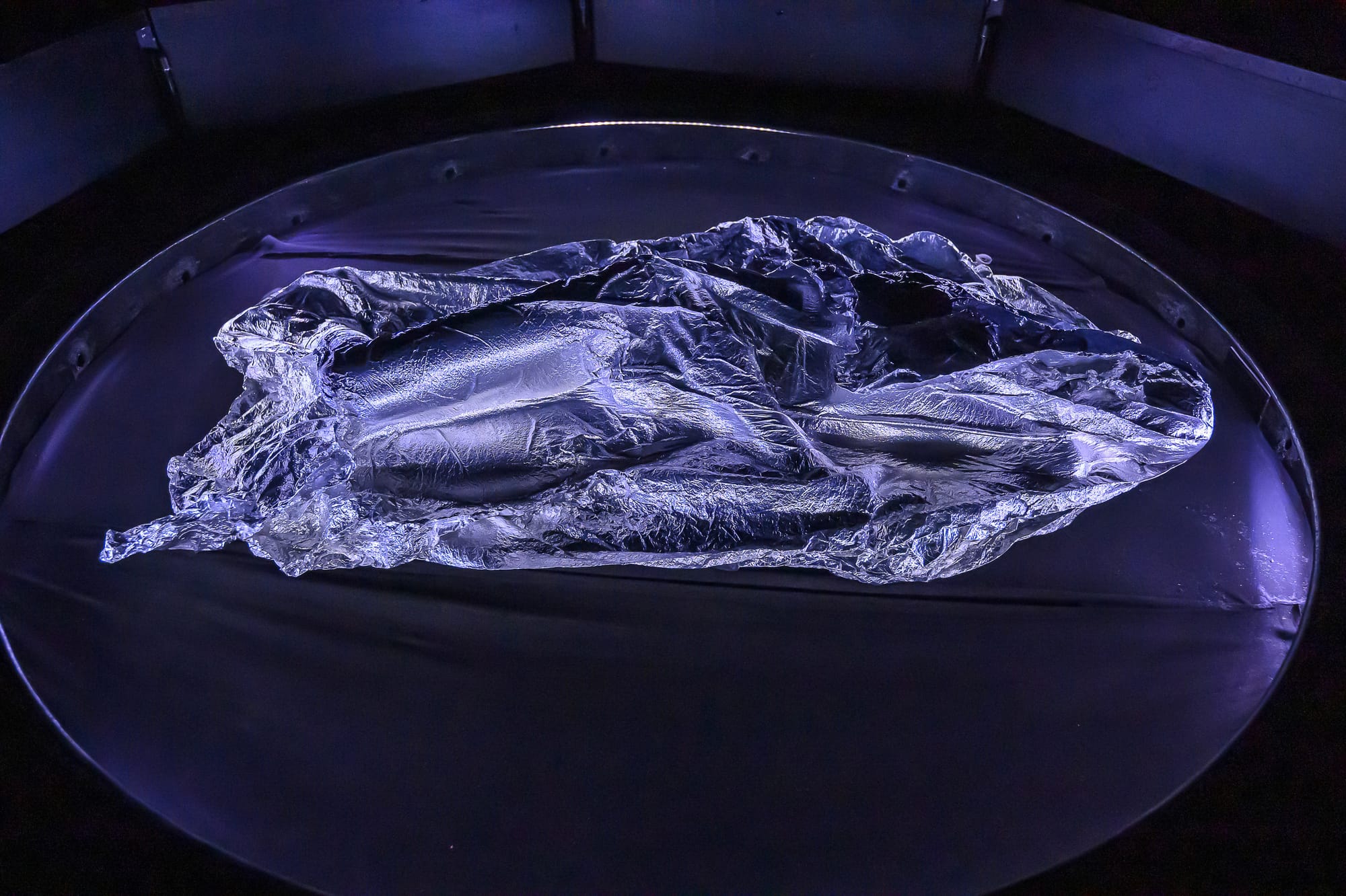

In L’Absolu, he explored the disappearance of objects on stage by filling the space with micro-particles, manipulating perceptions of emptiness and presence. This concept was inspired by Tarkovsky’s philosophical pursuit of the absolute, which Boris interpreted through embodied natural elements. In the piece, objects are treated not as passive props, but as active partners or extensions of the performers’ bodies, making absence and materiality central to the creative process.

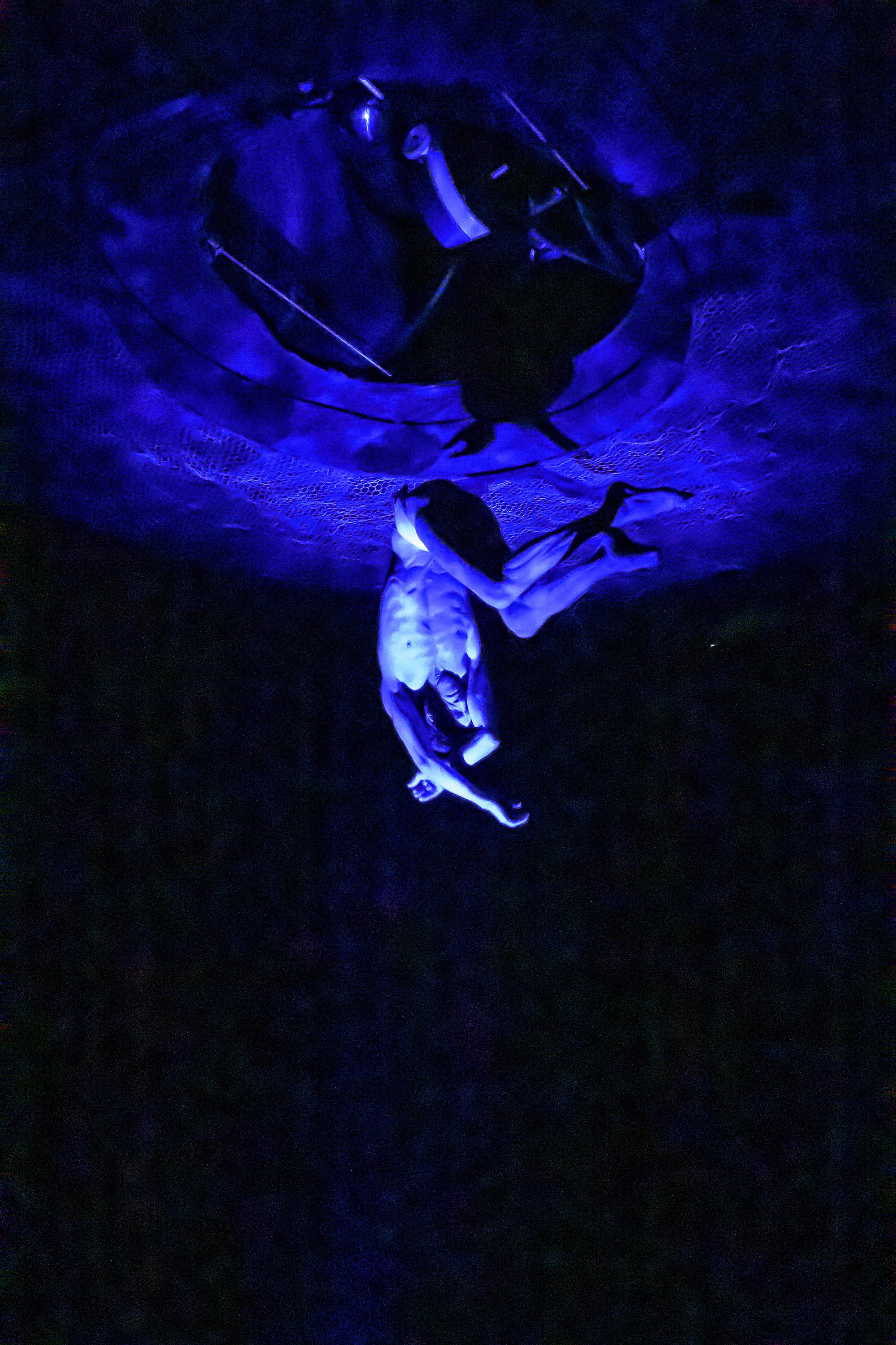

Anatomie du Désir, the show he is currently touring and presenting at Theater op de Markt 2025, is hosted in a big top called Panopticum, conceived as a full anatomical theatre. Boris began with a scenographic concept inspired by anatomical dissection. Initially imagining an intimate, darkened canteen where audiences would eat together, the project evolved into an exploration of invisible, cosmic forces and their influence on desire, mood, and perception.

He designed an extremely constrained performance space—a two-meter dissection table—embracing limitation as a source of creativity. When explaining this approach, he draws parallels with tightrope walking, where apparent freedom exists only through strict constraint, and with painting, where boundless expression is framed by the edges of the canvas.

Anatomie du Désir explores themes such as the place of women as objects of the patriarchal gaze, the role of the artist as the object of the spectator’s gaze, and the repetitive, almost fetishistic labour of artists seeking to affect their audiences. In the piece, he focuses on precision and refinement. By using electrodes to make invisible stimuli visible, the intention of viewing pain and injury as inherent aspects of circus practice is evident.

Always questioning the rules of objects’ use, Julian develops long-term relationships with his materials, while Boris stages them as existential elements within immersive spaces. What unites them is a shared drive to push the boundaries of circus practice, expanding what scenography can mean and do.

For Julian, scenography emerges through accumulation, crafting, and care, with objects shaping the performer as much as they are shaped. Boris, by contrast, transforms space itself into a perceptual and emotional environment, where architecture, atmosphere, and objects become active agents that absorb both performer and spectator. Seen together, their artistic approaches illustrate how contemporary circus scenography moves beyond decoration, becoming a medium of thought, sensation, and shared experience.