“I believe I can fly” “I believe she could fall” Contemporary Circus Dramaturgy and the Perception of Risk

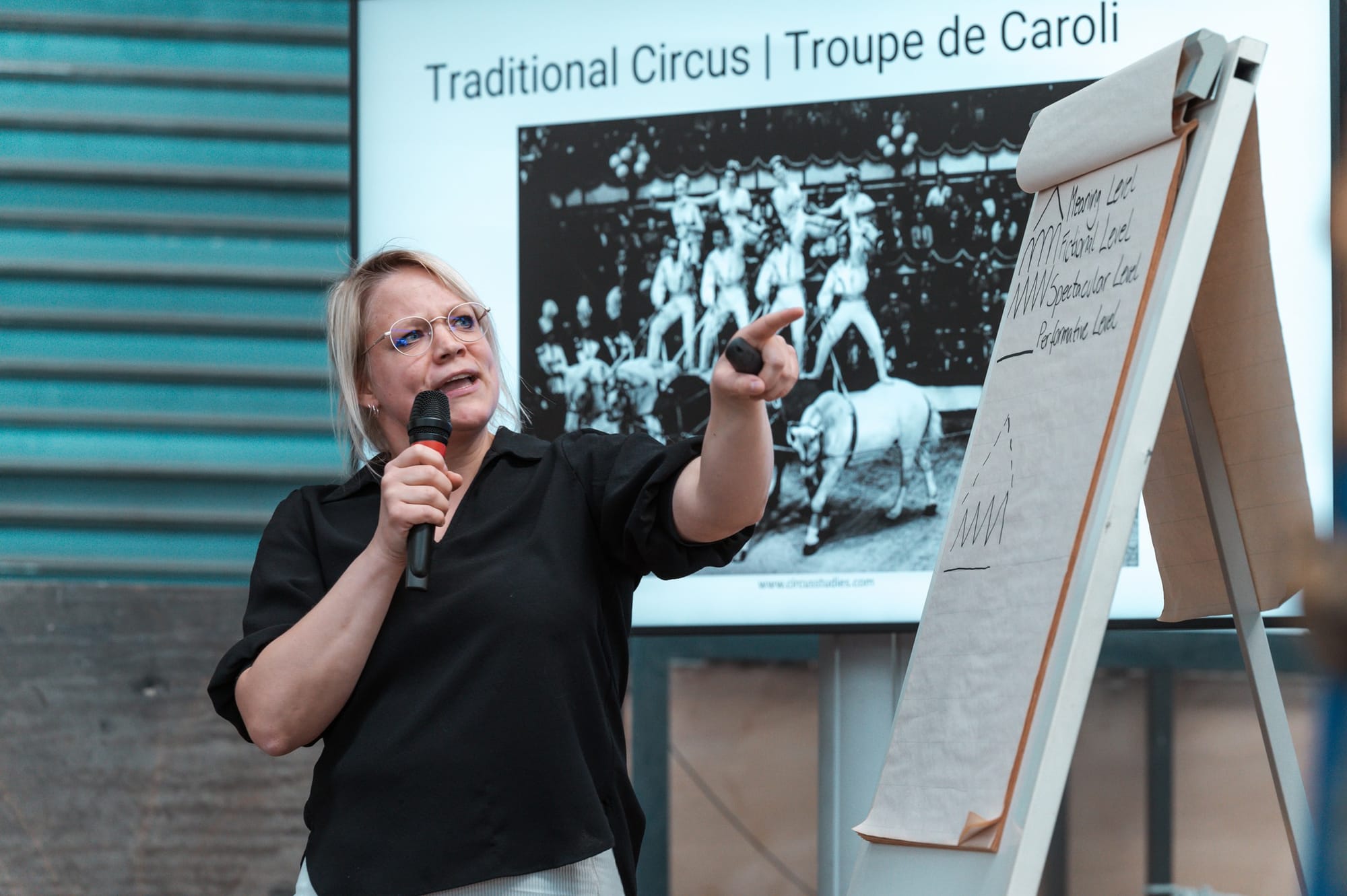

On 10th April 2024, I was invited as a keynote speaker for the international conference Circus - a safe(r) space for danger, the first conference on safety in the European circus sector in Antwerp (Belgium) during MAD Festival and MAD Convention organised by Circuscentrum, Ell Circo D’ell Fuego and MAD Festival. This text is a reproduction of my keynote. The presentation can be accessed at the bottom of the page.

Welcome, and many thanks for the invitation!

This lecture derives from my first monography entitled‚ Readings of Contemporary Circus. A dramaturgy’ [1] was published in German in 2020 [2] and will be published with Routledge in English this year. The main questions of the book were: How do contemporary circus performances create meaning? Are there generalizable characteristics despite the diversity of aesthetics and styles? What is the difference between traditional, new and contemporary circus? My interest in these questions derived from a need to take contemporary circus as an art form and a relevant object of (academic) research seriously. Just as much as an art historian would ask: “What is the specificity of an impressionistic painting?” or a theatre scholar would ask: “What are the characteristics of the theatre in the Victorian era”, I wanted to understand the main characteristics of contemporary circus performances. I aimed to comprehend which elements distinguish these performances from the traditional and new circus, just as much as impressionistic paintings are distinguished from expressionistic paintings.

In circus, we tend to distinguish the different forms of circus by referencing changes in practice and administration, such as the absence of animal acts or a new generation of artists who are not sprouts of circus families but graduates of state-recognized schools, or a general reference to narrativity. Those definitions quickly come to their limits: Baro d’Evel, Cie Hors Système, Cie Equinoctis, or Cie Sacékripa are companies commonly defined as contemporary circus but perform with animals. Furthermore, all three forms of circus are coexisting. It is thus difficult to (only) assign them to a specific timeframe. One objective of my PhD thesis was to revise the historiography of the circus so that it is no longer based on structural and administrative changes. Instead, similar to art historiography, the focus is on how the techniques of performances have changed.

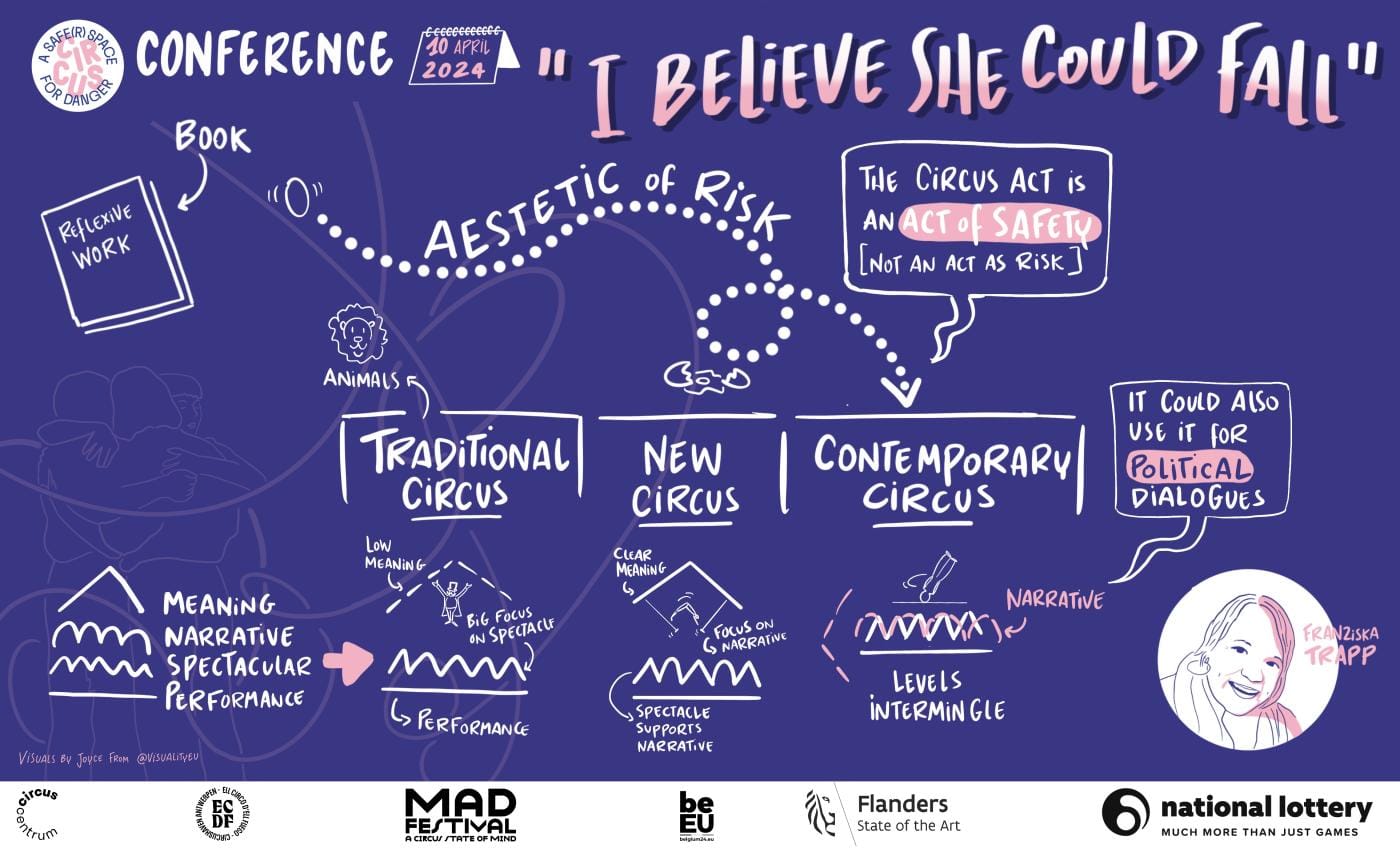

And, this is where the notion of RISK comes to play. Within this talk, I would like to defend the hypothesis, that it is the specific use of the aesthetic of risk within the process of meaning creation, that distinguishes traditional, new and contemporary circus performances.

I would lto do a little experiment!

For me, this little experiment beautifully visualises the circus’ relation to risk: The circus is, in reality, a “performance of safety”. And nevertheless we – as spectators – perceive it as inherently dangerous. This is dedicated to the fact that we think, that circus is dangerous. Or at least more dangerous, than high-impact sports: An athlete at the Olympic games and an acrobat in a circus perform the same trick. However, the audience perceives their presentations in completely different ways. While we observe the first to discover if the trick has been performed to perfection, we watch the latter to see whether the trick can be performed at all, or even fails.

Important in this context is the frame through which we watch a performance.

Let’s take a deeper look. How is risk staged in traditional, new and contemporary Circus? How is an aesthetic of risk created? How do narrativity and risk relate? [3] I need to expand a little on this. How do literary texts create meaning? Let's take Aesoep’s fable of the raven and the fox as an example. On the one hand, there is a textual level: “Once, the Raven saw a piece of cheese in a window, and grabbing it in his beak, flew off quickly to a nearby tree, there to savour it and eat it in peace....” This leads to a diegetic or fictional level, on which we follow the interaction between the raven and the fox in our imagination. And, third, this alludes to the level of meaning, the moral of the fable: Pride comes before a fall. Let’s transfer this idea to circus performances: In Circus, we deal with four different levels combined differently in traditional, new and contemporary.

Traditional circus performances

Traditional circus performances are fundamentally based on a spectacular level' establishment; a diegetic level is not created; and the meaning level can only be deciphered post hoc. The Troupe Caroli of the Cirque Bouglione could be used as an example. It was broadcast on the television format “Les Pistes aux Étoiles” on March 9, 1969: Through the Babylonian structure, cymbals, and drum rolls use, the only level established is the spectacular level. Signs on the performative level are not chosen for their meaning but for their attractiveness. No diegetic level is established. Although the crowns, which are part of the costumes of the female acrobats are reminiscent of princesses, within this act they don’t serve to establish a fictional world but serve as well to underline the super-humanity and thus the spectacular level. Furthermore, no meaning level is established. The interpretation of the traditional circus as a means to demonstrate human dominance and superiority is deciphered only post hoc. Only post hoc, traditional circus can be read as a symbol of anthropocentrism.

New circus performances

New circus performances are characterised by alternating between the spectacular and the diegetic level. I would love to use Cirque de Soleil’s KOOZA as an example: When marketing KOOZA (a new circus performance), Cirque du Soleil does not follow traditional programs. The performance is described with the following words: “KOOZA is an innovative journey viewed through the perspective of The Innocent, an endearing yet naïve clown looking for his place in the world. A mystery item is delivered to The Innocent one day when he is flying his kite. The self-discovery journey of The Innocent, who is miraculously transferred to a bizarre but exotic world, is followed in KOOZA under the watchful eye of an enigmatic trickster with remarkable abilities.” The focus is not artistic achievement but the narrative unity of the piece, or the diegetic level. But what roles are played by the technical performances of the artists, the acrobatic interludes of the colourful mythical creature, and the group acrobatic act? In these cases, the use of circus techniques establishes the diegetic level. The artistic movements of the protagonist are a characteristic of the depicted character, the acrobats are part of the fantastic fictional world, into which we are invited by the mythical creature. The artists' performances are not primarily attributed to the phenomenal bodies of the artists but received as the abilities of the mythical creatures. This also explains the dominance of the fantastic fictional world in the performances by Cirque du Soleil (Saltimbanco, Alegria, Mystere), into which the artists' abilities fit without any problems.

In this context, the aesthetic of risk is less visible.

There is one major objection regarding this modelling: The performance La Perle du Bengale (1935, Cirque d’hiver) by Cirque Bouglione which tells the story of a British lady being kidnapped by a Hindu prince presents the same structure as what is considered a New Circus piece in this modelling. However, New Circus did not even exist. And yes: the modelling aims to differentiate between Traditional, New and Contemporary Circus based on their technique, not based on a historical timeline. With this reasoning, La Perle du Bengale would be considered a New Circus show. Why then using the notions of traditional, new and contemporary circus? Why not a usespectacular, narrative, and postmodern circus? I for my part, always like to start my research and argumentation from the practice. Within the circus scene, we are using these notions while referring to the performances that function in the manner presented above. I therefore refrain from creating neologisms.

Contemporary circus performances

To conclude: The specific use of the aesthetic of risk is fundamental for the differentiation of traditional, new and contemporary circus. If we consider these differences in the levels of circus performances, circus history can be written as a procedural history. Circus history would record not only structural and administrative changes, such as the absence of animals, the new generation of performers, or narrativity, but in analogy to art historiography, it would focus on changes in the performances themselves.

“I believe I can fly” “I believe she could fall” - Presentation

References

[1] Trapp, Franziska: Readings of Contemporary Circus. A Dramaturgy, Routledge 2024.

[2] Trapp, Franziska: Lektüren des Zeitgenössischen Zirkus. Ein Modell zur text-kontext-orientierten Aufführungsanalyse. De Gruyter 2020.

[3] This part of the lecture was explained freely with the help of drawings and while referring to diverse examples. If you want to explore the topic please see Trapp, Franziska: Readings of Contemporary Circus. A Dramaturgy. Routledge 2024. Chapter 3.