An Insight: Take Care Mental Health Conference through the Bodies of the Initiative Feminist Circus

Hi,

Before we start, I’d like you to ask yourself:

Is this the right time to read this article? Why do you want to read it? Do you feel obliged to do so?

To be honest about our current feelings must be one of the first steps toward taking care of ourselves, and thereby toward mental health.

If this is the right time, there’s a second thing before we continue:

The following article offers an insight from the perspective of the Initiative Feminist Circus, with insight into the Take Care - European Conference on Mental Health and Well-being in the Circus and Performing Arts Sector, which was organised by FEDEC, CircusDanceFestival Cologne and Around About Circus, and took place at the CircusDanceFestival on 7th June this year.

The Initiative Feminist Circus is an association based in Germany, emerging from a movement that started in 2020. It now serves as a platform for feminism, activism, and support in feminist issues.. The Initiative has been collaborating with and supported by the CircusDanceFestival since 2020 and was represented this year not only at the conference but also with an on-site info booth and a “get-together” event.

The conference is part of FEDEC’s broader ongoing efforts to bring unspoken issues into open conversation. Over the past two years, FEDEC has invested significant time and resources into SPEAK OUT – Together for a Safer Circus. I had the opportunity to attend one of the workshops and became part of a process that aims to make circus schools safer for everyone. Likewise, the conference reflects CircusDanceFestival’s ongoing efforts to make its festival more accessible. The festival's awareness concept is updated annually, and the team also continues to educate themselves on topics such as mental health.

I’d like to start my experience report on the festival with a quote from Gaia Vimercati, one of the panel speakers. She put into words something deeply important - both when writing about events like this and for me, especially when I find myself overwhelmed with anger or frustration about how slowly society moves toward equality and freedom:

“It’s not about finding solutions, it’s about shaping the process.”

So let’s take a look at how we shaped the process at this conference:

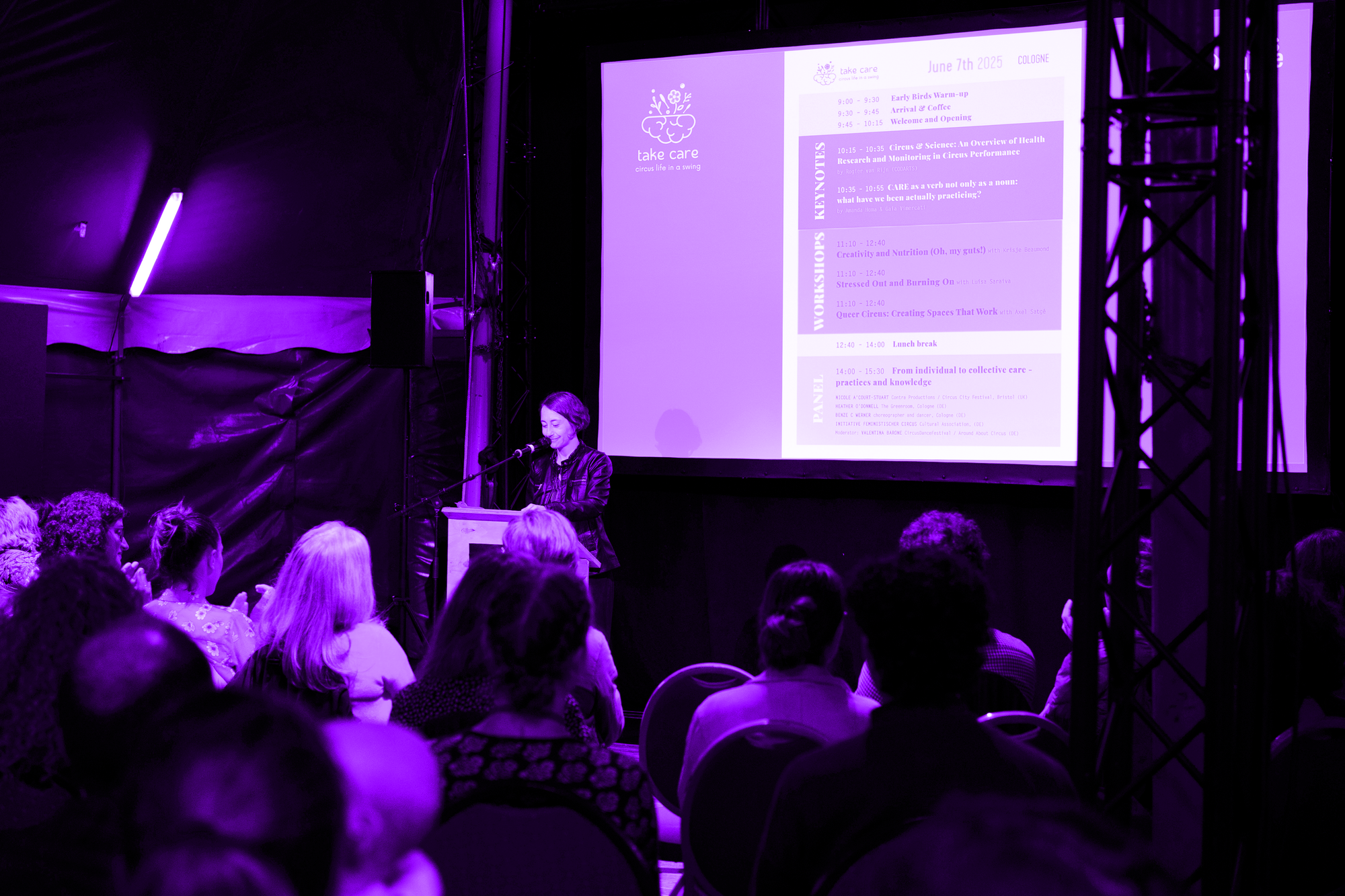

The day began with an Early Bird movement session led by Tim Behren, the CircusDanceFestival’s curator. It was an example of a thoughtful way to break down existing hierarchies by sharing a movement space to start a networking day. After coffee and a collective gathering, the day officially began with welcome talks by the institutions that organised the conference.

In his welcoming speech, Tim Behren emphasised, among other things, that the honest use of one's own resources is a practice that needs to be developed. At the same time, he invited us to be curious about what is possible when we work together:

“Let's see what we can do, but please only do what you can do.”

Valentina Barone gave us an overview of the context in which the conference is situated. She talked about the idea that festivals can become ‘spaces of care’ and how we could develop practices for sharing knowledge across generations. Finally, Sarah Weber and Isabel Joly from FEDEC gave an outline of all cooperation partners and invited the participants to approach them for feedback and possible collaborations.

Valentina mentioned in her welcome speech the familiar term often used in mental health discourse: “work-life balance.”

I wondered: Is this even the right concept for a field in which a lot of people say, “Circus is my life”? So then: what is “work”? And how do we find balance? Wouldn’t it be better to ask a different question entirely, to find truly revolutionary concepts?

For example:

How can our love for circus become healthier? How can we create shared spaces, like festivals and training environments, that don’t require balance in the first place?

Luzie Schwarz, CircusDanceFestival’s production manager, also presented the Awareness concept at the start and said that they want everyone to feel comfortable. CircusDanceFestival, compared to nearly all other circus festivals in Germany, has a well-developed awareness policy and makes a visible effort toward inclusivity. Still, these spaces remain predominantly white. Everyone present had thin, conventionally shaped bodies. Everyone understood English, and it seemed like everyone was fine to sit on chairs.

Why is that so? Why, as a simple example, do we assume that everyone likes to sit in a chair? *Did you know that even furniture is often shaped by patriarchal structures?

Just like the “comfortable” temperature in air-conditioned rooms is based on the average middle-aged European man, spaces are built for them unless we question every last detail. Even the ability to sit still in a chair and listen for two hours is a learned skill—not accessible to everyone. This is not only a matter of gender. During the first part of the conference, I thought about my friends with ADHD. I wonder if it would be possible for them to attend.

[*This is a question inspired by the book of Rebekka Endler, The Patriarchy of Things - Why the World Doesn't Fit Women, 2021]

A few thoughts:

Could we offer different ways of sitting? What if we took breaks more often? Could we incorporate opportunities for movement in between? Could brief talks or introductions be supported with PowerPoint slides? And wouldn't these tools be relaxing and good for EVERYONE - not just for people with other needs? Just because we can endure things does not mean we have to. What else can we learn to make these spaces truly diverse?

The welcome talks were followed by two keynotes: one by Rogier van Rijn, Circus & Science: An Overview of Health Research and Monitoring in Circus Performance, and the other by Amanda Homa and Gaia Vimercati, CARE as a verb, not only a noun: what have we been actually practising?

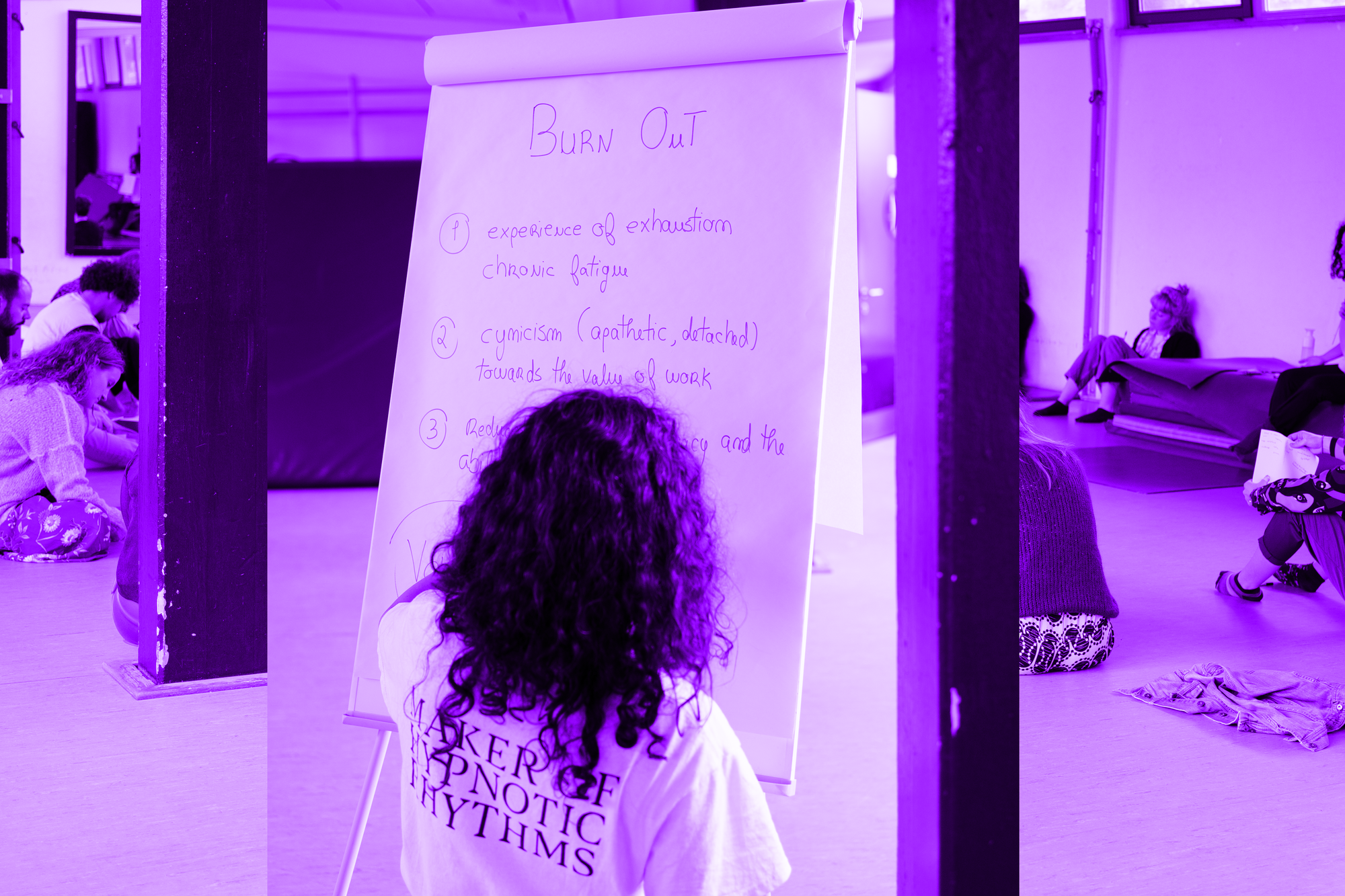

Rogier explained their approach to monitoring injury rates at school and the ways they try to support their students. With my background in sports science, I could follow their reasoning well. But with my feminist heart and my relationship with body image and eating disorders, I started to feel uneasy when I saw diagrams and statistics used in the context of mental health and body examinations.

In the second keynote, Amanda managed to articulate this unease. She and Gaia emphasised that we must be careful not to confuse “taking care” with “taking control.” Diagrams and charts lead us to categorise ourselves and our performance on scales in order to compare them. Furthermore, in a patriarchal system, they are also repeatedly used to define the ‘norm’.

Later that day, I also spoke with a student from the school Rogier was referring to, and the person described how these approaches seemed to benefit the institution more than oneself. This would have been an interesting view to discuss, in relation to the aims and how it reached the students.

I wondered:

Do comparisons - whether with ourselves at another point in time or with others - ever make us feel truly better?

For comparisons to help and motivate, we need to be aiming for the same goals. We have to want the same. Forgetting that everybody is unique, has different bodies, and has completely different opportunities in the patriarchal and capitalist society we have built. Gaia and Amanda discuss this idea of equality in their keynote when they talk about Hegemony:

“Hegemony is one of the most important values that capitalism and colonialism rely on. It is through making everyone believe that we should desire the same lifestyle, have the same models, and that every person should replicate them on their own, that those systems keep functioning and growing.”

Their keynote was a bold and gentle manifesto, a reminder of the context in which this conference was taking place. I was very interested in how the non-white people reacted to their keynote. One person placed a hand on her heart, and others snapped their fingers in agreement. I cannot speak for their experience, but it was a powerful reminder of how rare and vital it is for some truths to be clearly named, especially in spaces shaped by whiteness.

Another highlight: Gaias and Amanadas matching T-shirts with ‘Take’ and ‘Care’. They concluded their keynote with this statement:

“Healing spaces are the ones that don’t lie to you about pain.”

And I ask myself:

How can we stop lying about pain, when pain is something so heavily romanticised in circus?

After the keynotes, participants split into three workshops: Creativity and Nutrition (Oh, my guts!) with Krisje Beaumond, Stressed Out and Burning On with Luísa Saraiva and Queer Circus: Creating Spaces That Work with Axel Satgé.

Returning to the core question of this article - how do we shape the process? - I appreciated the thoughtful curation of themes around mental health. Luísa Saraiva stated clearly from the beginning: working in the circus sector puts you in a high-risk group for stress. Her workshop primarily consisted of practical exercises designed to reduce stress. I saw the impact and resonance on the face of my IFC colleague when I met her at lunch: she was enthusiastic and said she had gained many practical tools for her daily work.

My other colleague, who attended the nutrition workshop, sat visibly irritated next to me and mentioned terms like “good” and “bad” food.

Considering the idea that healing spaces don’t lie about pain, we need to remember that an extremely large number of people in the circus world suffer from eating disorders (defining eating disorders not just as anorexia, etc., but as any tense feeling about food and body image). And through the dominant narrative of white, thin, well-toned bodies – not just in circus, but everywhere – society has a strange idea of the normality of how our bodies should look to be presentable. Circus bodies are disciplined down to the smallest detail - even if they tell us about freedom. Diagrams and charts that categorise food as “good” or “bad” - like comparisons - are not helpful for mental well-being. Furthermore, failing to distinguish between menstruating and non-menstruating bodies in terms of nutrition can lead to problems and risks. Menstruating bodies require an adapted diet to meet the physical demands of circus life. From a scientific point of view, there are of course reasons to make performance, body and changes measurable. And this can also be useful when considering mental health. However, the transfer to everyday life and presentation should be done with great awareness and sensitivity.

I attended the workshop on queer spaces. I appreciated the intention behind it: to create guidelines for more queer-friendly structures in the circus sector. However, the vocabulary, questions and approach in this workshop led to irritation and pain in present queer hearts. Carlos Landaeta Meneses, one participant, finally found the words for it:

“The moment you try to define queerness, it’s gone.”

The conversation about ‘queer people’ and their “needs” led to a reproduction of the feeling of ‘being different’. It made me feel like I was too much again, my needs too complicated.

The idea of a manifesto to ensure security for queer people feels like a very Western and controlling way of trying to “solve” things. Socialised in Western systems, with Christian patterns etched into our bones, we always search for solutions - for absolution. We want to act, confess, and feel better. But we cannot “solve” this.

What we can do is learn to stand the pain. To hold it, not trying to make it disappear. To be aware that our bodies, by their very presence, can be violent to others, and to develop a practice to reduce this. As white people, as men, as academics - it is our task to reduce our violence. The internet is full of resources and people who have decided to do educational work. So, maybe a good starting point could be to find ways to educate ourselves and not expect that people (who already endure the oppression we perpetrate) do additional educational work with us.

Again and again, throughout the conference, I felt irritated. Maybe I misunderstood something? Why was I hurt by so many approaches that seemed to head in the right direction?

Then I asked myself:

Do we have the same goal? Or is the question we need to ask ourselves first: what problem are we actually addressing? In the example of circus schools, are ankle injuries really the problem we should focus on? Or rather, the physical and psychological pressure caused by the circus school system itself, which also leads to physical injuries? And more broadly: is this the product of our exploitative capitalist reality? What are we truly willing to change? What are we prepared to give up so that others can participate?

The conference ended with a panel curated by Around About Circus, with Nicole A’Court Stuart (Contra Productions/Circus City Festival, Bristol), Heather O’Donnell (The Greenroom, Cologne), Benze C. Werner (choreographer and dancer, Cologne), and Amanda Homa, invited by the Initiative Feminist Circus. They shared field experiences and best-practice examples. Less an exchange but a very fruitful presentation of the experiences and working methods of the panellists with courageous approaches on how circus can be a medium to collaborate with the community, how we can create spaces to heal and how we can find our way back to our bodies in small ways, like asking:

“What does a yes feel like in our body?” [Benze C Werner]

Valentina concluded the conference, reminding us that one of the crucial things to learn is to recognise when you can no longer continue - and become active then.

At the end of the day, my head was buzzing. My body, heart and mind tried to harmonise the impressions. The hurt and the hope. The frustration of having the same discussions again and again, and the gratitude of meeting people who are just as frustrated as I, and thus to feel a connection.

These mixed feelings were captured on Sunday at the IFC Network event: in keeping with our theme for the year, Support, we asked ourselves how we can support one another. Not by asking “what is needed”, but beginning with the question:

What is easy for you? What do you enjoy doing, and how can you use these skills and abilities for the community?

There were nearly fifteen people from different European countries. It was a great pleasure to experience so much feminist change in concentrated form and to know that all these people will share their passion in their communities. We left the tent with a sense of connection. Even after stepping out of the ribbon network that had physically bound us together at the end of the workshop, we still felt united by our shared concerns and our aim to amplify feminist voices and visibility in the circus sector.

“It’s not about finding solutions. It’s about shaping the process.”

And this is why it is so wonderful that this conference is just one part of a broader program, through which FEDEC, CircusDanceFestival and its partners strive to keep these issues in focus.

Thank you for your time. Finally, I would like to extend an invitation: Lie down for five minutes. Or, simply sit still, if lying down isn’t an option.

Since my residency with Amanda Homa, I have started and ended every training session with resting. That has changed a lot. Give it a chance.